EDIT: There is a follow-on post here: David Marquet: Turn the Ship Around

In the past couple of decades, we went through an “empower your people” fad. We saw work teams in world class companies that were largely self directing, surprisingly well aligned with the overall goals of the organization, and getting things done.

“Well,” we thought, “since empowered teams are obviously more effective, we’ll empower our teams.”

They brandished their wand uttered some wizard’s chant, and bing! empowered their teams.

They brandished their wand uttered some wizard’s chant, and bing! empowered their teams.

“What did you expect to happen?”

“We expected our newly empowered teams to self-organize, get the work done, plan all of their own vacations and breaks, and continuously improve their operations on their own.”

“What actually happened?”

“Work ground to a halt, people argued and squabbled, quality went to hell, and labor hours went up 20%”

“What did you learn?”

“That empowerment doesn’t work.”

Which is obviously not true, because there are plenty of examples where it does. Perhaps “Empowerment doesn’t work the way we went about it” might be a better answer. That at least opens the door to a bit more curiosity.

The last place I would expect an experiment in true empowerment would be onboard a U.S. Navy nuclear submarine.

Take a look at this video that Mike Rother sent around a couple of days ago, then come back.

A U.S. Navy submarine skipper isn’t generally inclined to swear off ever giving another order. It runs against everything he has been taught and trained to do since he was a Midshipman.

I’d like to cue in on a couple of things here and dissect what happened.

First is the general conditions. I think he could do this just a bit faster than normal because everyone involved was sealed inside a steel can for six months. Just a thought – groups in those conditions tend to have a lot of team cohesion.

But the mechanics are also critical. He didn’t just say “You are empowered.” Rather, this was a process of deliberate learning and practice.

What is key, and what most companies miss, are the crucial elements that Capt. Marquet points out must be built as the pillars of an empowered team.

Let’s put this in Lean Thinker’s terms.

As the Toyota Kata wave begins to sweep over everyone, there is a rush to transition managers into coaches.

“What obstacles do you think are now in the way of reaching the target?”

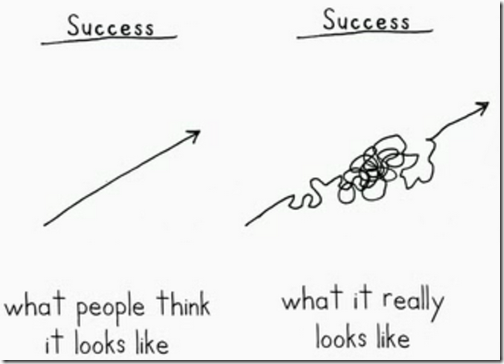

See the illustration above.

Competence and clarity.

I am going to start with the second one.

Clarity

Or… where the hell are we trying to go?

Capt. Marquet points out the critical element of commander’s intent. I learned this during my decade or so as a military officer (U.S. Army). When preparing operations orders, I had to clarify the overall commander’s intent. Why? So that when everything went to hell in a handcart, everyone knew what we were trying to get done even if the how to do it entirely broke down.

What that means in the lean thinking world is “What is the business imperative” or “What is the challenge we are trying to achieve?” If nobody knows “why,” then all they can know is “what” and that comes down to “implement the tools,” which, in turn, comes down to “because I said so” or “Because we need a 3 on the lean audit.”

Doesn’t work. Never has.

But I’m beating that topic to death right now, so I want to move the pillar on the left.

Competence

In my book, that means “The leader has a good idea how to do it.”

What does that mean in practical terms? In Capt. Marquet’s world, it means that, fundamentally, the crew knows how to operate a nuclear submarine. Additionally, it means they understand the ramifications of the actions they are taking on the overall system, and therefore, the contribution they are making to achieving the intent.

It doesn’t matter how clearly anyone understands what they are trying to get done if they have no idea how to do it.

In Lean Thinking world, competence means a few things.

- The leader knows how to “do the math.” She understands the overall flow, the impact of her decisions on the system and the overall system.

- The leader / coach has a good understanding of at least the fundamentals of flow production, and why we are striving to move in that direction.

While these things can be taught through skillful coaching, that implies that the coach has enough competence to do that teaching.

But if the coach doesn’t fundamentally grasp the True North, or doesn’t consistently bias every single conversation and decision in that direction, then Clarity is lost, and Competence is never built.

We end up with pokes and tweaks on the current condition, but no real breakthrough progress.

Day to day, this means you are on the shop floor interacting with supervisors and front line managers. You are asking the questions, and guiding their thinking until they grok that one-by-one flow @ takt is where they are striving to go.

In my Lean Director role in a previous company, I recall three distinct stages I went through with people calling me for “what to do” advice.

First, I gave them answers and explanations.

Then I transitioned to first asking them what they thought I would give as an answer.

Then they transitioned to “This is the situation, this is the target, this is what we propose, this is why we think it will work, what do you think?”

“Captain, I propose we submerge the boat.”

“What do you think I am thinking?”

“Um… you would want to know if it is safe?”

“How would you know it is safe?”

In other words…

What are you trying to achieve here? How will you know?

So here is a challenge.

If you are a line leader, especially a plant manager, take one week and utterly refuse to issue direction to anyone. Ask questions. Force them to learn the answers. Test their knowledge. Have them teach you so they must learn.

You will learn a lot about the competence of your team. You will learn a lot about your own clarity of intent. Try it on. No matter what, you will learn a lot.

at to do (clarity), and know how to do it (competence), then leaders generally have no issues trusting that the right people will do the right things the right way.

at to do (clarity), and know how to do it (competence), then leaders generally have no issues trusting that the right people will do the right things the right way.