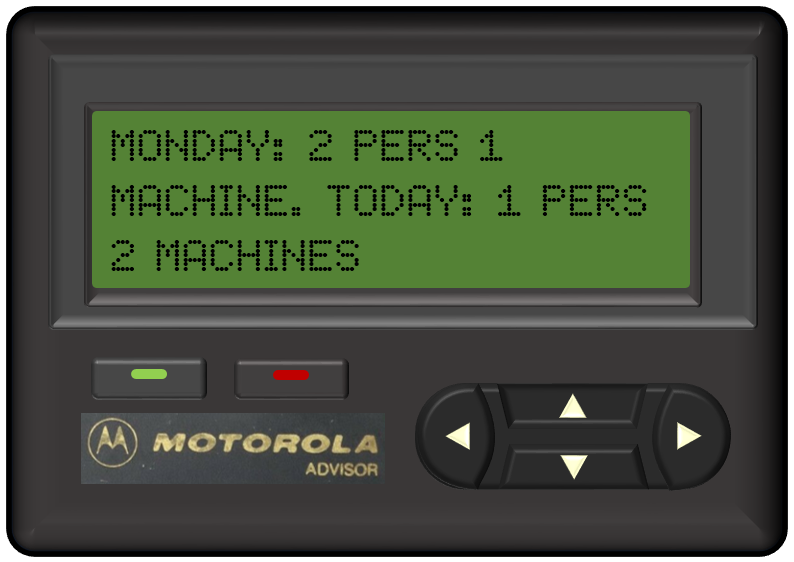

MONDAY: 2 PERS 1 MACHINE. TODAY: 1 PERSON 2 MACHINES

On a Thursday afternoon in the summer of 1997 I sent that pager message (remember pagers?) to Rick from the factory where I had spent a week working with Mr. Shimura of Shingijutsu and Reiko, his interpreter.

I knew that Rick would be wrapping up a class teaching the basics of kaizen events to a group of suppliers and if I were lucky, he would see the pager message and use it as a reinforcement to the participants. Rick and I usually alternated teaching that class, sometimes we taught it together. We were good work partners, finishing each others’ sentences and the mutual respect was very high.

I was on-site at another supplier. We were there to help them take some first steps toward “lean production.” Our goal, at least the idea, was that we would work through the process of making significant improvements with the thought that they would learn enough to try it themselves.

This was not my first visit – the episode with Mr. Iwata that I relate in my third post to this blog had happened there a couple of months earlier, and that visit had resulted in my company offering up Mr. Shimura’s time on our dime.

This may well have been “an offer they couldn’t refuse” and I’m not sure everyone there saw it as help. We were from their 800 pound gorilla customer, they had trouble making on-time deliveries, and sometimes that isn’t the kind of help that you want. From their perspective their biggest customer had people who knew their way around a factory spending days on their shop floor and, most certainly, ascertaining how much more productivity was possible if only, well, the buyers squeezed them hard enough. It didn’t really work that way, but it had worked that way in the past, so who could blame the suppliers for thinking this was a more sophisticated way to audit them?

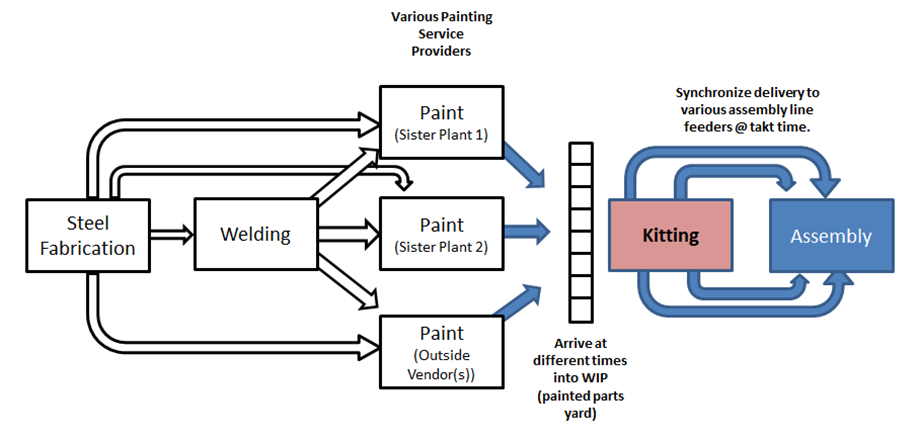

Anyway, we had worked through the week to carefully look at the tasks involved to unload, load, and machine a single part on a large linear milling machine. Mr. Shimura was there asking questions, not so much from curiosity but to direct my eyes. I’m sure he already knew the answers. As we dug into the timing, it became clear that there was enough operator waiting time as the part was being milled that a single operator could, theoretically, unload and load an adjacent machine – operating two of them at once.

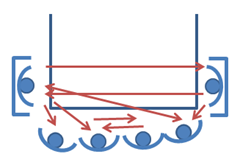

So we carefully worked out the chorography required to make it work, and on Thursday mid-day it all came together. The work was flowing, the parts were flowing. It was really a thing of beauty.

Friday morning we would report out the week to management, and Friday afternoon I would head to the airport to go home to Seattle.

But I had some worries as well. Although the company President, and the VP of Operations were supportive, their support was along the lines of welcoming everyone into the plant, making it clear they were happy to see us, attending the final report-out and endorsing our efforts.

I was still pretty knew at this. I was making the transition from teaching classes and running simulations to making real change in real factories (that weren’t mine!). I was really fortunate to have a lot of 1:1 time with Mr. Shimura and Reiko. I asked questions, he patiently taught me how to use the standard work combination sheet, and other nuances of kaizen and flow production. I got a lot more out of that week than the supplier did simply because I was there spending time with Mr. Shimura and taking advantage of every second I could. I had 1:1 time because none of the supplier’s managers were seeking him out to learn from his vast experience.

Some quotes I will never forget: “If I see something is hand written, then I know at least one person has read it.”

“If parts that are in tolerance don’t fit, it is a problem with the tolerances.”

(Walking through the shop) “Does this company lose a lot of money?” Reply: “No, they are very profitable.” “Then their prices are too high.”

In the end, though, I am equally certain that come Monday morning the work sequence we had so carefully worked out – at great expense to my company for my time, my travel, Mr. Shimura, his interpreter, and others – was never repeated again.

Why not?

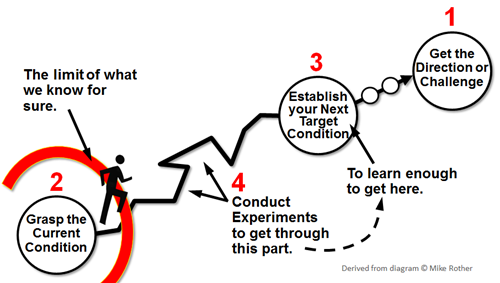

Well, we can all blame “management commitment” because that is really easy to do. But I put equal weight on our paradigm of improvement at the time. The idea that, in 4 working days we could institute a change that flew straight against the operational and cultural norms of the company and expect it to last any longer than until we were out the door was, well, ludicrous.

Why should we expect anything different?

It is ludicrous in any company, whether this work is being brought in from outside or internally generated.

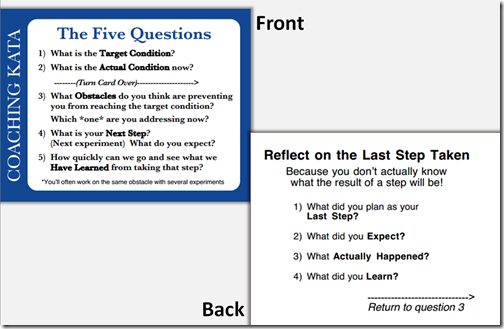

The people who have to manage the daily work, whether they were involved in this exercise or not, have no paradigm for dealing with the myriad of issues that are bound to be surfaced after we pulled all of the buffers out of the material and the time. Yes, it can work, IF we understand the conditions required for success, and IF we pick up right away when those conditions aren’t there and IF we respond to fix it very fast. Then, yes, it can work.

It will be more time and trouble than it was before, though, unless the next things are also done.

For at least some of those issues – maybe not all of them, but always working against a couple of them – seeking out why those issues happened and dealing with the causes.

Just to keep this tiny two-machine “work cell” operating in this large factory would have eventually engaged every support system they had.

That’s the whole point, actually, of a model line. It isn’t building the model line. It is what you have to fix in your systems to keep it going.

Many years later I spent a week on another company’s shop floor with their internal kaizen team and getting an andon / escalation process up and running was the only thing we were working on that week. That process is just as important, if not more, than the baseline work of flow. Because without it, your flow will fall apart.

This is the part of the process that engages people. Putting in the baseline process is the easy part. Fielding the problems that flow surfaces – that takes changing the day-to-day routine in the workplace, and is a lot harder. That is where the culture change comes into play. Actually it is more than engaging people. It engages specific people: This is the part that must engage the leaders. They must lead, guide and coach process of working through all of the issues so stability can be reestablished. Then challenge the team to get to the next level.

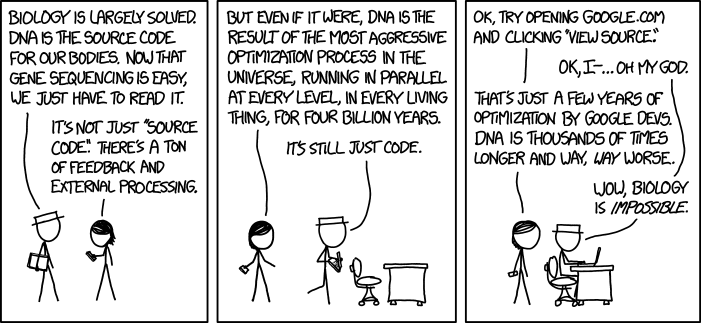

But all of that is what I know now. I had the knowledge back then, but not the deep understanding.

So – I am thankful for that week because my understanding of what I had been teaching for months easily doubled… twice in those few days.

I was back there a few more times, they even gave me a badge (which I still have somewhere) so I could let myself in. One time I spent two straight weeks there. They were good people.

But we were applying work to the technical systems, and never really dealing with their default responses to problems, their culture, the way they went managing their daily work.

I know so much more today it is actually humbling to write this. And I still have a lot to learn. We all do.

The company I was working in? They were sold, and sold again. I think they are still in business, but I wouldn’t know anyone there.