Last week’s post about The Improvement Kata and DMAIC prompted some interesting discussions during the week, and I’d like to share some additional thoughts.

Before you read on, reflect a bit on what you think I totally missed. Does this post go where you expected it to? Does it confirm, or refute, your hypothesis about whether Mark was right or not?

What I Totally Missed!

I was too focused on the structures within the Improvement Kata and trying to draw lines between them and DMAIC.

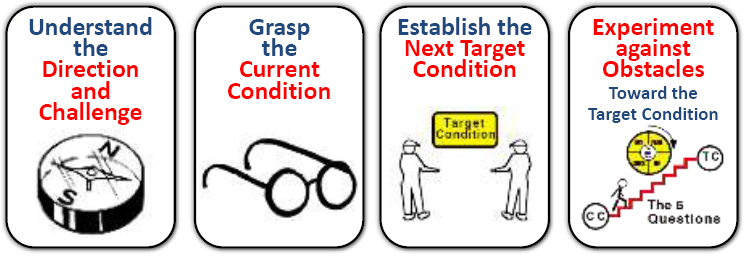

Though we talk about the high-level structure of the Improvement Kata as steps, I think it may be more useful in this discussion to think of that structure as representing four phases* of any improvement or problem-solving effort.

Let’s take the term “Improvement Kata” out of the discussion because, right now, I am finding it distracting. Instead, let’s look at problem solving and improvement in general.

Phase 1:

Regardless of the specific approach we are using, we want to begin by clearly understanding what problem we are actually trying to solve, and what “solved” looks like.

This is the case whether I am looking to improve a process to new levels; whether I am trying to hit some kind of KPI goal; whether I am trying to understand the root cause of a problem; whether I am seeking to develop a new product; whether I am trying to influence someone’s decisions or behavior. Diving into proposing solutions without this understanding can easily turn into an exercise in frustration.

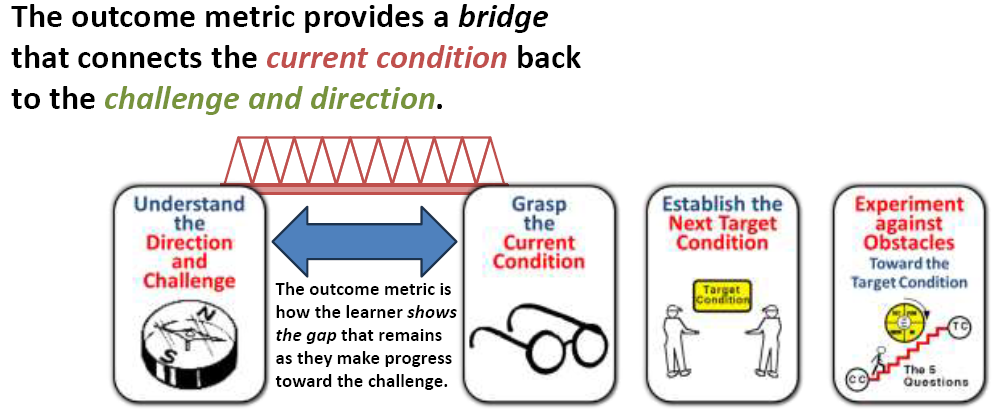

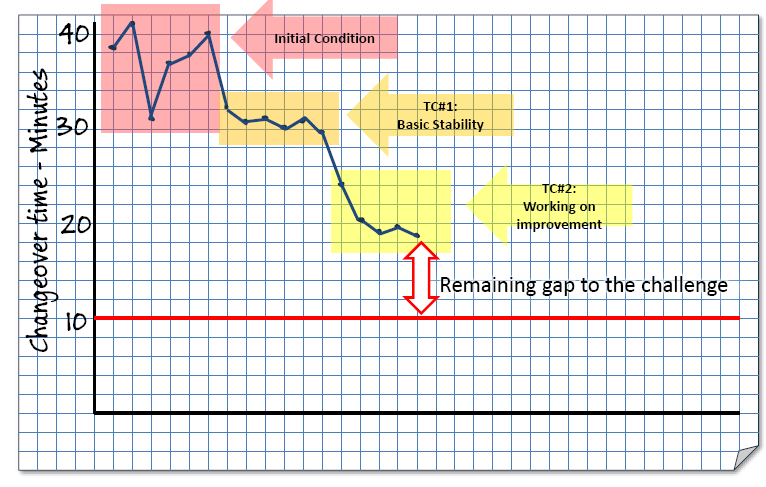

As soon as that desired outcome is understood, it’s a good idea to start tracking it against the goal so we can see what progress we are making.** I tend to default to a run chart for this.

Phase 2:

Once the problem is well defined, the next phase is gaining understanding of what is actually happening so that we can explain any gap between the current condition and the ultimate goal. Depending on the specific high-level problem, we may be trying to understand the relationship between the underlying process and its performance; the relationship between product design characteristics and product performance; the relationship between the user interface and errors; the relationship between the work culture and someone’s behavior; the relationship between the characteristics of whatever we are investigating and the phenomenon we are trying to influence.

We are working to understand the factors that drive the dependent variable of outcome.

Even as we gaining that underlying understanding, we have to be aware of hard-wired human nature to assign meaning to anything we are perceiving. It is really easy to fill in gaps and jump to conclusions. It is important to resist that temptation. Any conclusion being reached should trigger another question along the lines of, “What evidence do I actually have (or need)?” and prompt another level of inquiry.

Phase 3:

Even with my caveats above, the line between understanding what is happening and assigning meaning is more blurred than most practitioners would care to admit.

The formal process of making meaning is analysis. But as we go, it is very common that things we want to address will emerge. Sometimes the thing we need to address is another level understanding. My favorite quote from Steve Spear is, “The root cause of all problems is ignorance.” There is something we do not understand well enough.

At this (some?) point we can propose a hypothesis: If I change x, then I expect to improve (or learn more about) y.

Our analysis may find lower level, operational, metrics that are driving the outcome. For example, if the outcome is a level of productivity, we will probably find some combination of total cycle time and / or sources of delay that are driving output. Or quality yield. Whatever it is, we are starting to build a hypothesis of cause-and-effect between the outcome and the things that are driving it.

We set an intermediate goal based on that hypothesis, perhaps sketch out how the process needs to look, or changes in the product that would be required. Then we look with more focus and ask, “What is making it hard to actually do this?” and propose what problems we might have to solve to get there.

The key is that we (think we) know what we want to try changing, what impact we think that change will have, and what problems have to be solved to make that change actually happen (and, once we prove it works, sustain).

Phase 4:

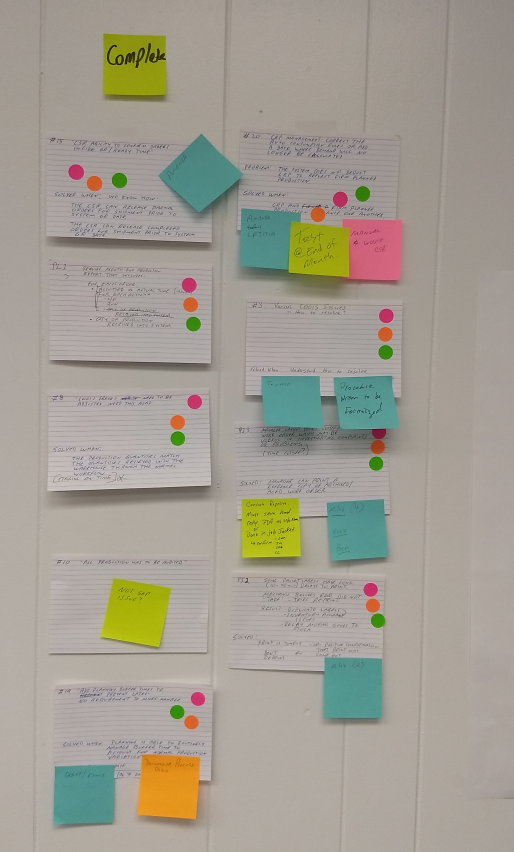

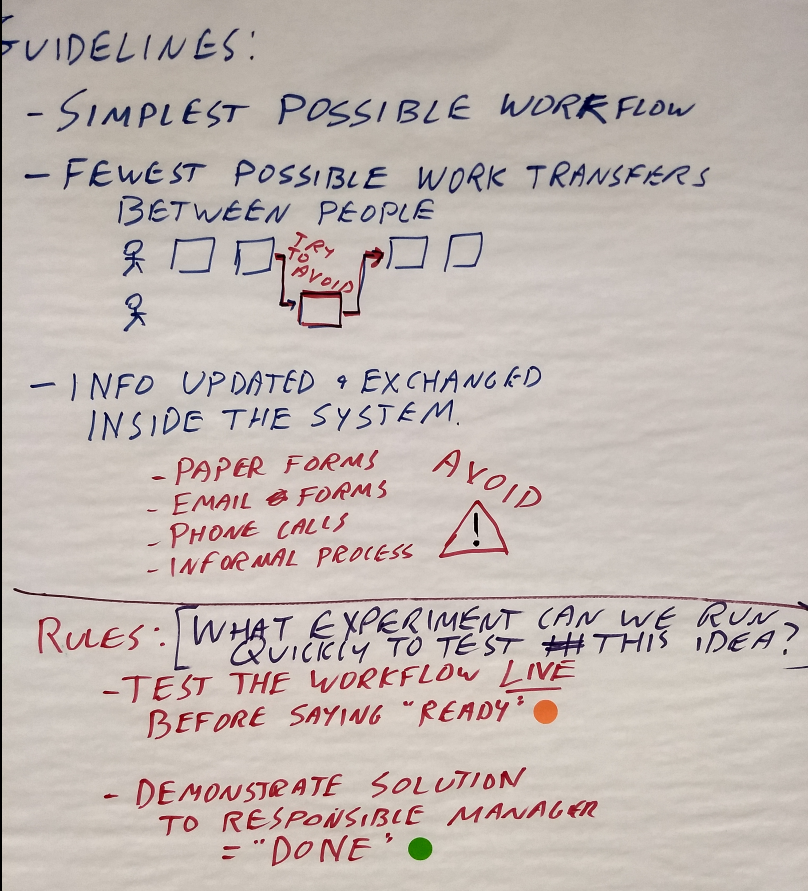

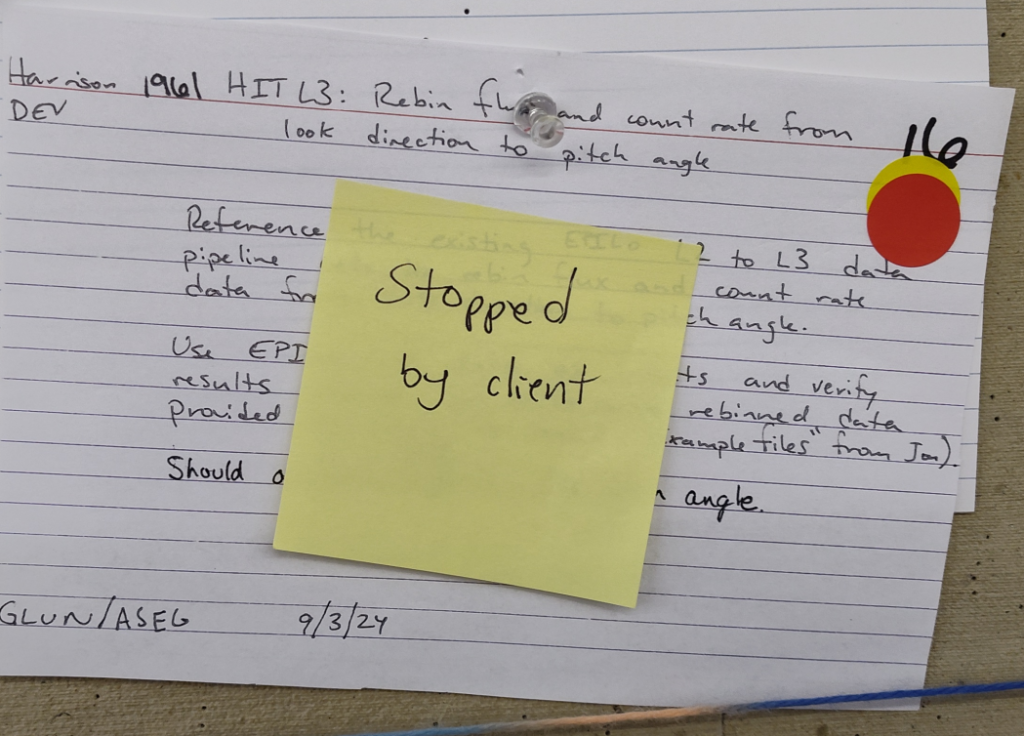

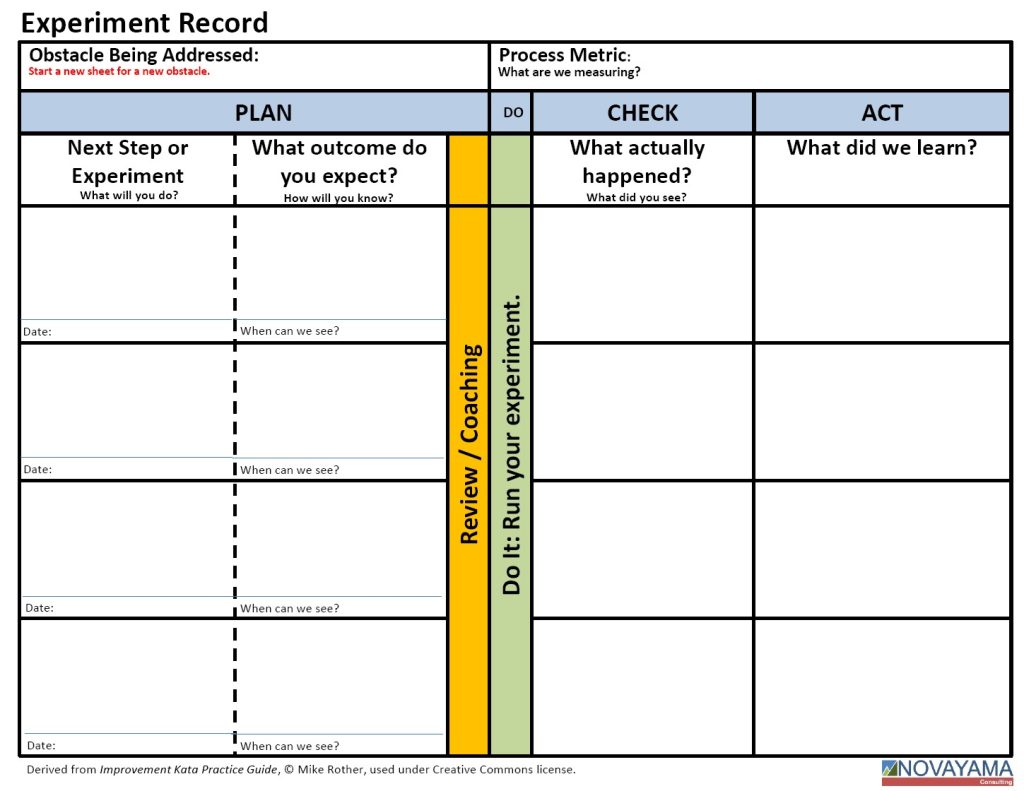

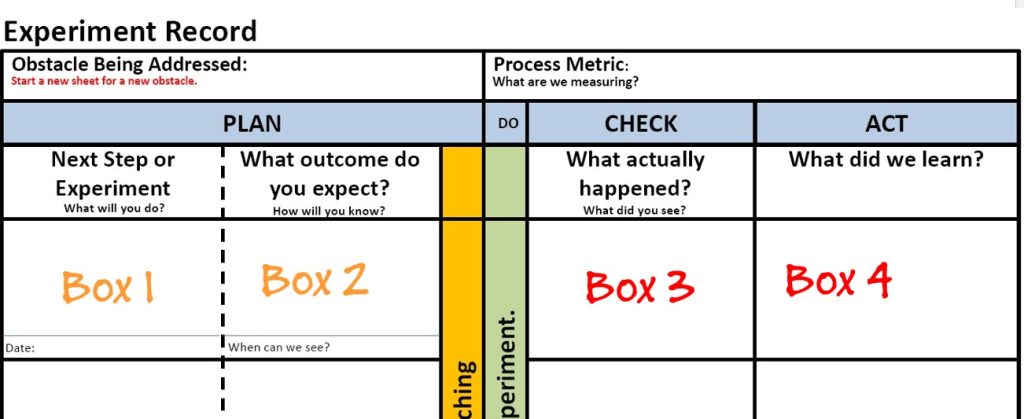

Then we can pick off one of those problems and start to propose solutions – though it is also common to begin with a need to learn more about it. But those proposed solutions need to be tested. So we propose any action we intend to take as an experiment: We are going to _____, and we expect that ( something we will learn ). That learning may be more information, it may be simply learning that this idea works, doesn’t work, or works in a way we did not expect.

As thorough as we have been, we will likely discover that our information is incomplete. That doesn’t mean we have been sloppy. It means that as we narrow our focus or start making changes we are very likely to discover things that we didn’t see before. It is critically important that the goal of learning takes precedence over proving we are right.

That learning may take us into a different domain than the one we started in. For example, we might be working on something like process cycle time and run into something about the engineering design of the product itself that is an obstacle to improvement. The process is agnostic – it doesn’t respect organizational or functional boundaries. Nor does it respect organizational politics. It just tells you what is in the way of making the change you want to make.

“You don’t have to like your reality, but you have to deal with it.” – Brian Bakke

Back to the top.

Regardless of how the specific approach is structured, reality usually makes it iterative, often at multiple levels. Each change I make is going to have rippling effects on the overall process. Each change is going to bring out more understanding in the obstacles. Even after I have a solution I am pretty sure will work, trying to get it into place and stable offers up a new set of problems. You haven’t solved the problem until the solution is in place as the new routine.

So even if you reach that initial or intermediate goal, there is probably more work to do. Go back to the top, review your understanding of the problem, re-confirm your understanding of the current condition (you may have to dig in again if you have been narrowly focused), develop a cause-and-effect on the CURRENT condition (not just the one you started with), and start working toward that – always anchoring changes are you go.

My Revised Hypothesis

To summarize, although my last post was trying to map DMAIC into the Improvement Kata steps, what I now think I am proposing is that all approaches to problem solving and improvement that work follow a similar underlying pattern. The mechanics may be different, the jargon is certainly different, but at the end of the way we are all trying to take a scientific, fact driven approach to gaining deep understanding before just twiddling knobs and changing stuff.

The Other Thing I Totally Missed

It is really easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the Improvement Kata is just another structure for problem solving. That is, honestly, because when we look at the Improvement Kata as a stand-alone process, it is. That is the other mistake I made.

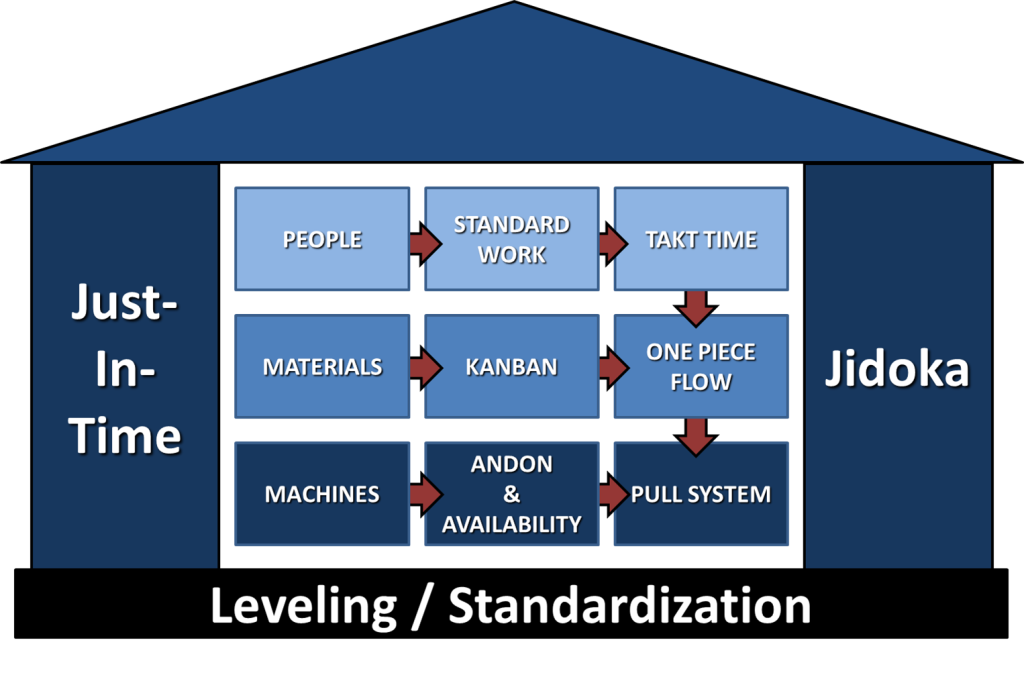

But the Improvement Kata is not intended to be stand-alone. It is one side of a larger structure.

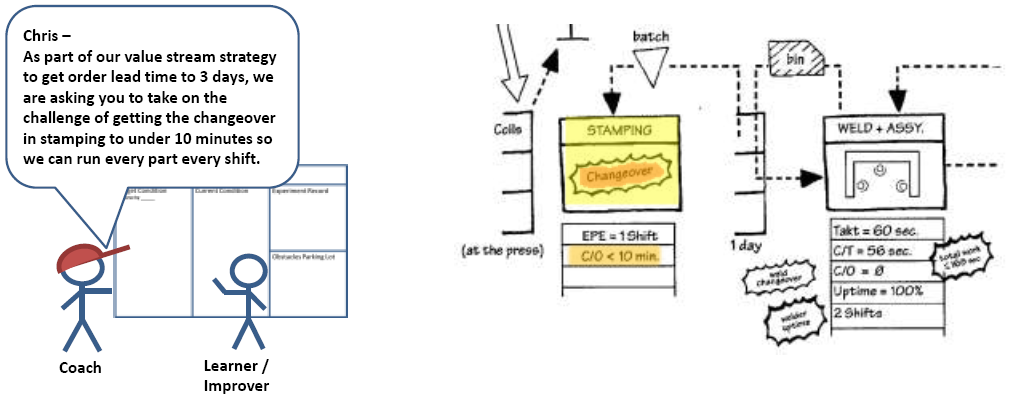

The thing that Toyota Kata brings in is that coaching is an inherent, embedded, part of the process.

Intended Outcomes

Going back to the origin of Six Sigma, before there were different colors of “belts,” the role of the “Black Belt” was that of the professional problem solver. They would find (or be assigned) a major problem to solve, and go through the process defining it, measuring it, analyzing it, proposing and implementing solutions, and leaving the stakeholders with a “control plan.” Yes, that is an oversimplification, but that is also what I have seen in the wild at a number of companies with active Sigma programs.

So I think the focus here is on how an expert practitioner goes about “solving the problem.”

This legacy goes back a lot further than Six Sigma – with industrial processes we can go at least as far back as Frederick W. Taylor’s (and others) work over 100 years ago. The structure of TWI Job Methods (which was heavily influenced by Frank Gilbreth who was, in turn, an acolyte of Taylor though he had some philosophical differences) is that of a supervisor working largely on their own to streamline the work.

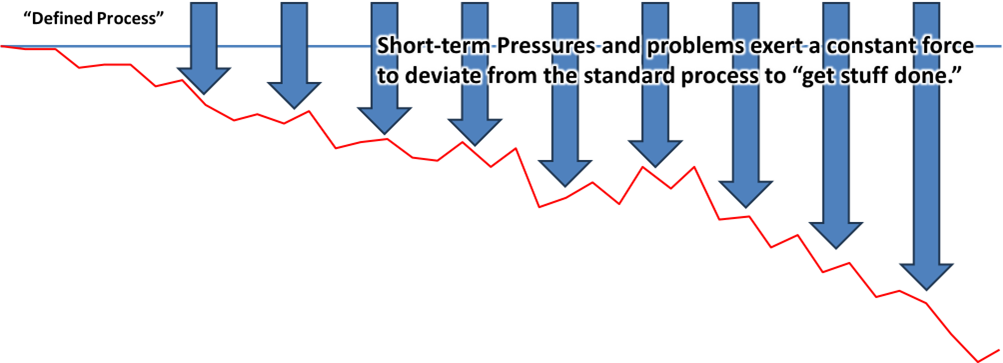

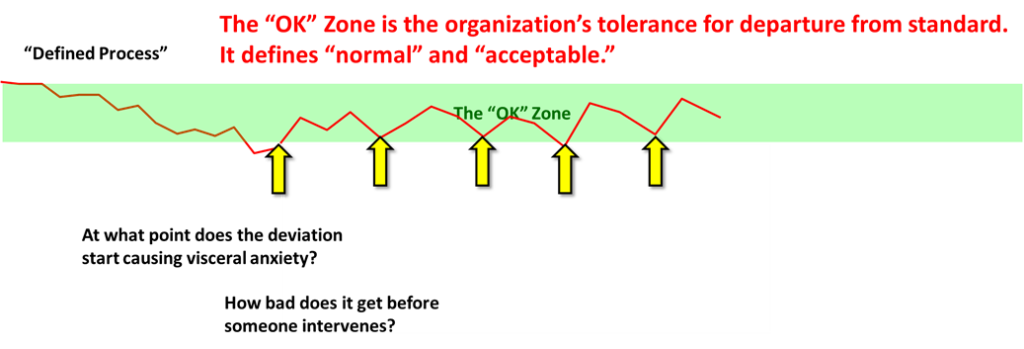

Regardless of whether it is DMAIC or something else (even traditional kaizen events), the classic approaches to improvement don’t have active, daily, coaching conversations built into their very structure. YES, it is absolutely possible to introduce them, but those structures are not there by design – except where they are.

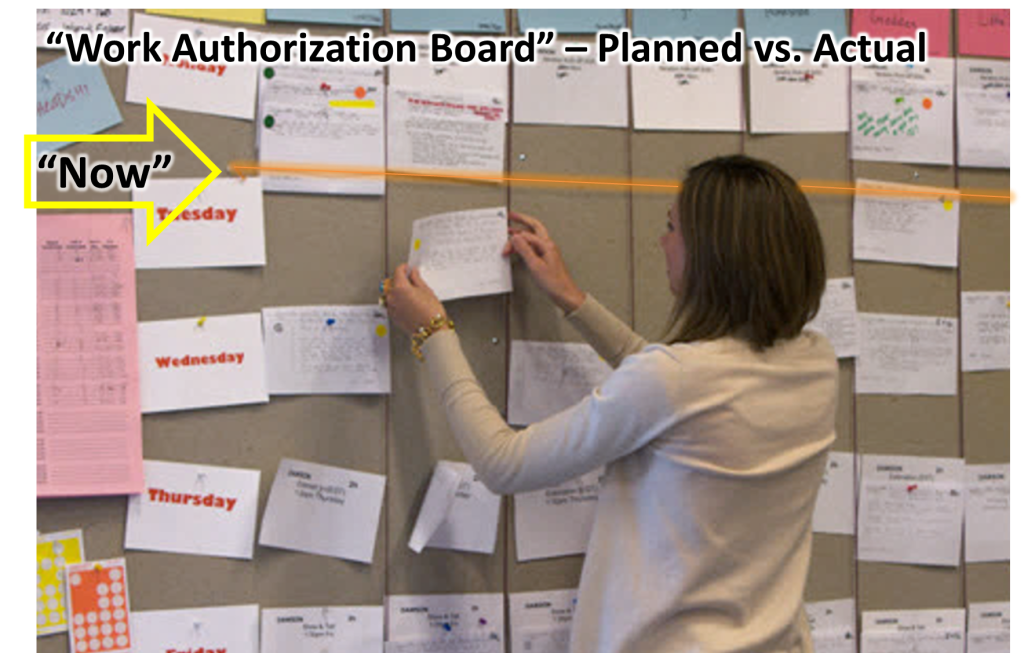

In his early research on Toyota’s culture, Steve Spear talks about them “creating a community of scientists.” Their day-to-day process of improvement goes beyond just soliciting ideas from everyone. There are structures to the process design, and structures in the conversations about improvement, that facilitate becoming a better problem solver.

Toyota Kata is the result of Mike Rother’s research into the nature of those conversations, and then (most importantly!), how other companies might structure THEIR conversations to learn to do this. (Toyota does not follow Toyota Kata! Nor has anyone (who knew what they were talking about it) every claimed they did. Toyota’s intrinsic, unseen routines were parsed out and turned into visible routines that others can learn by practicing the basics.)

What is Toyota Kata For?

Maybe the real question is who is Toyota Kata for?

The way the Improvement Kata steps are usually described in books and training material (mine included, at least up to this point) are as things for the learner (the problem solver; the improver) to do. And, yes, they are… but

This is still (somewhat) controversial within the Toyota Kata community, but I am continuing to reinforce my belief that the structure and specifics of the Improvement Kata are more for the primary benefit of the coach, especially someone who is just developing those coaching skills.

“Why don’t you go do a kata on that?” is good a way to assure that this won’t work any better than to say, “Hey, go do an A3 on that.” Those assignments are neither delegating nor empowering. They are more akin to abdication of any responsibility to develop the skills of the person you are asking to solve the problem.

It is the coach who asks the improver to use those Starter Kata tools. Here is my working example – drawing from my skiing metaphor, but this is true of any coach who is working to improve someone’s technical skill.

A long, long, time ago I took up skiing again after a 15 year hiatus. I quickly remembered why I had stopped – it was a real struggle. This time I resolved to get better and signed up for a half-day lesson at Whistler, BC.

The first thing the instructor (coach) had us do was ski down the hill and cut some turns while she watched. She was evaluating each of us against her internal reference standard of a “perfect turn.” But rather than offering general critique she gave each of us a specific drill – one thing to practice – that would help us get to the next level. Not to perfection, but demonstrably better than we started.

My working hypothesis is that she had a repertoire of those drills in her mind, and based on where she found our “threshold of knowledge,” she pulled one of them and assigned it to us to practice. Mine was a drill that forced me to keep my upper body facing straight down the “fall line” as my hips pivoted underneath me. I can say that, after about an hour of practice, it worked. I became a much better skier that day.***

What about a someone who is just learning to be a ski instructor? I imagine that part of their learning is going to be a baseline of those drills. “If you see this, then assign that.” It is enough to get them started as they learn and develop their coaching skills.

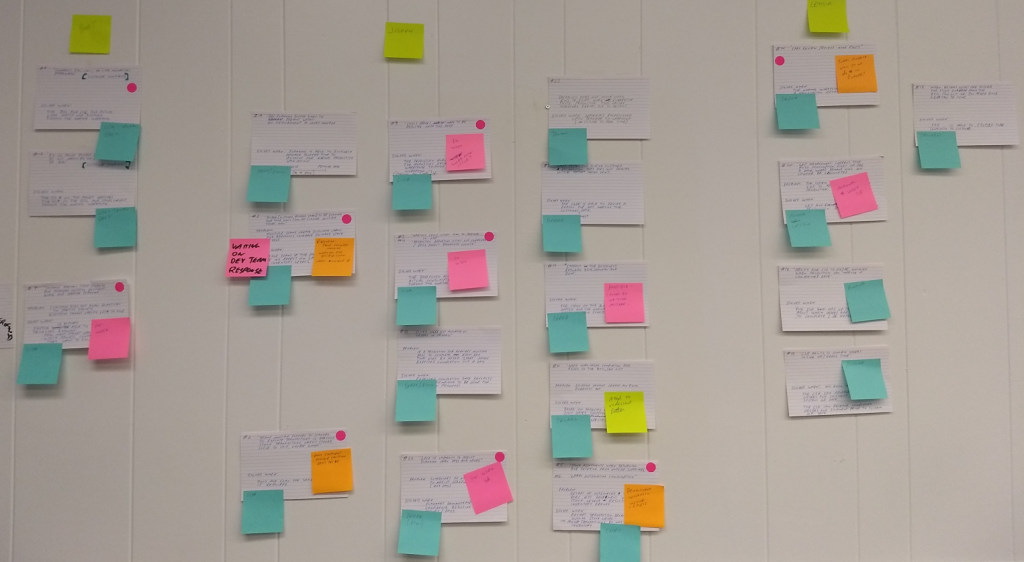

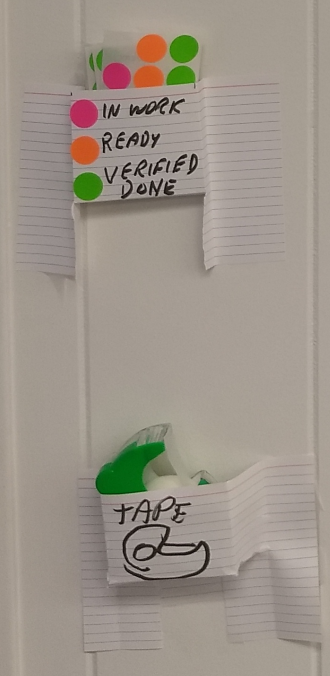

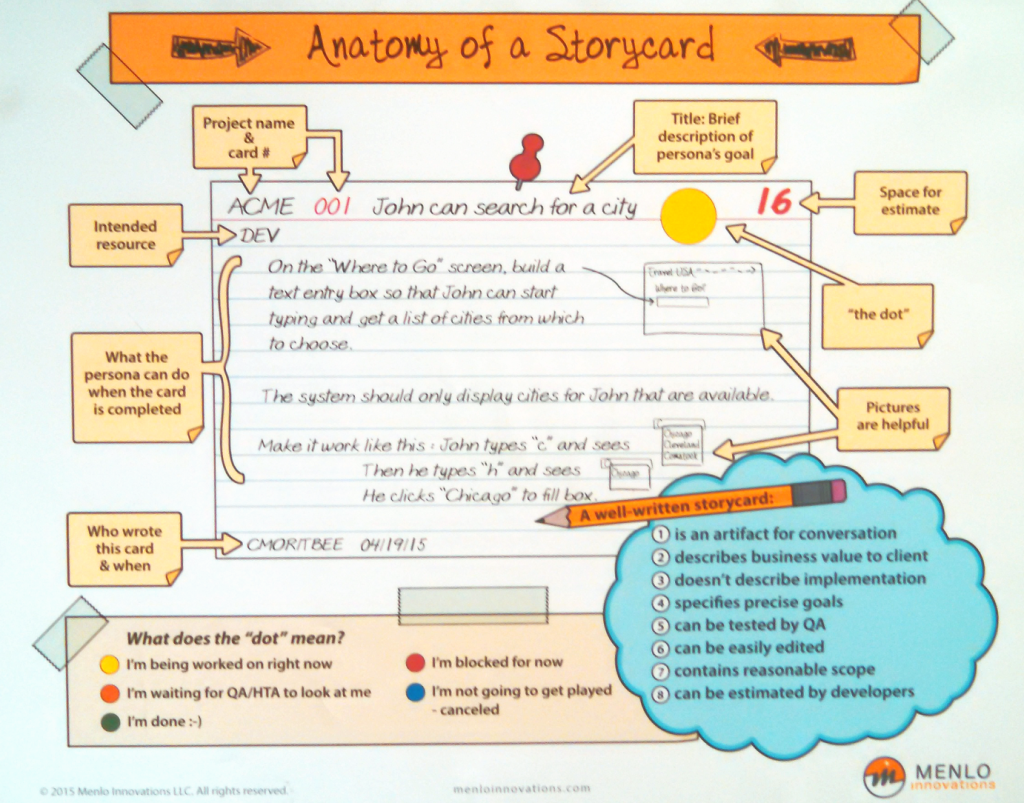

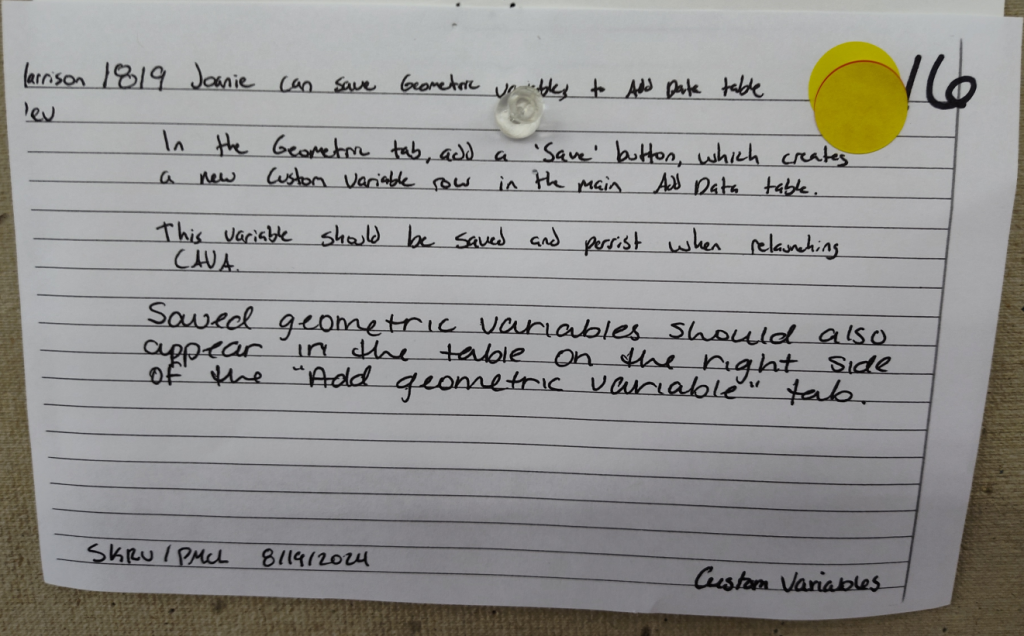

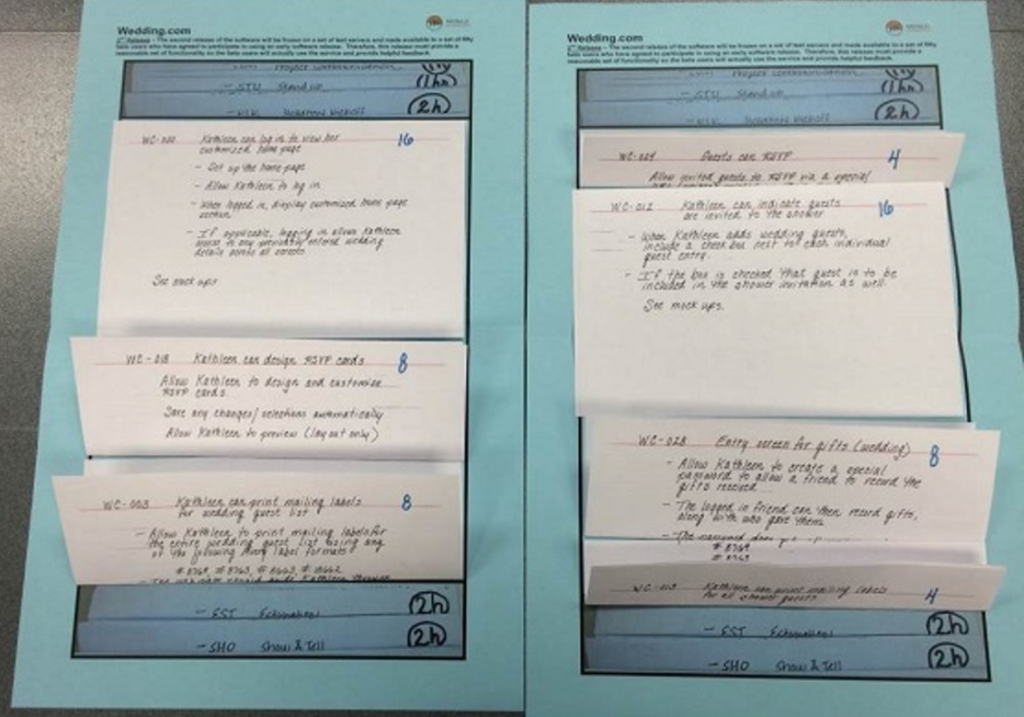

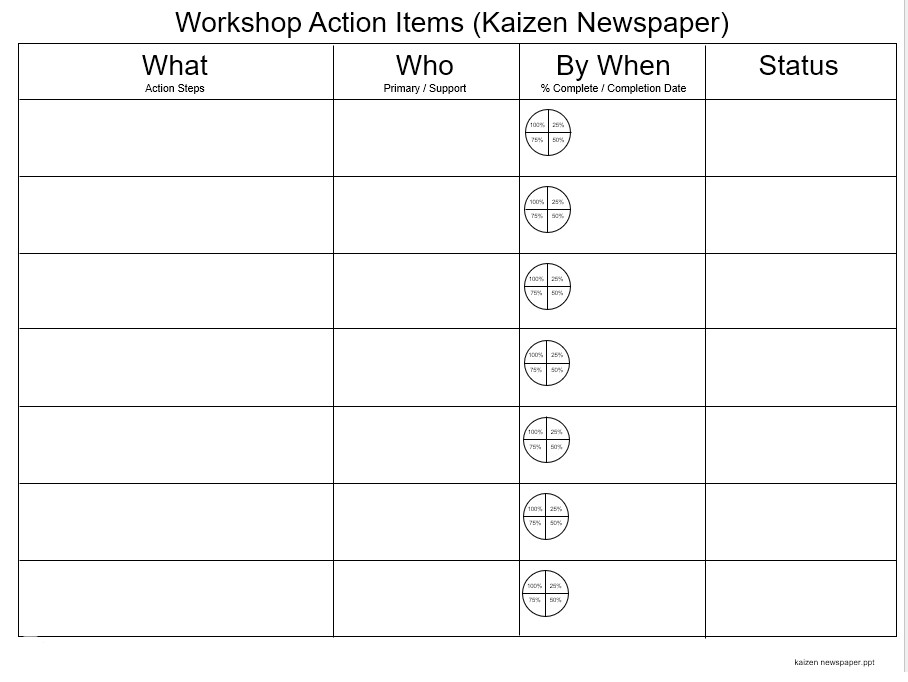

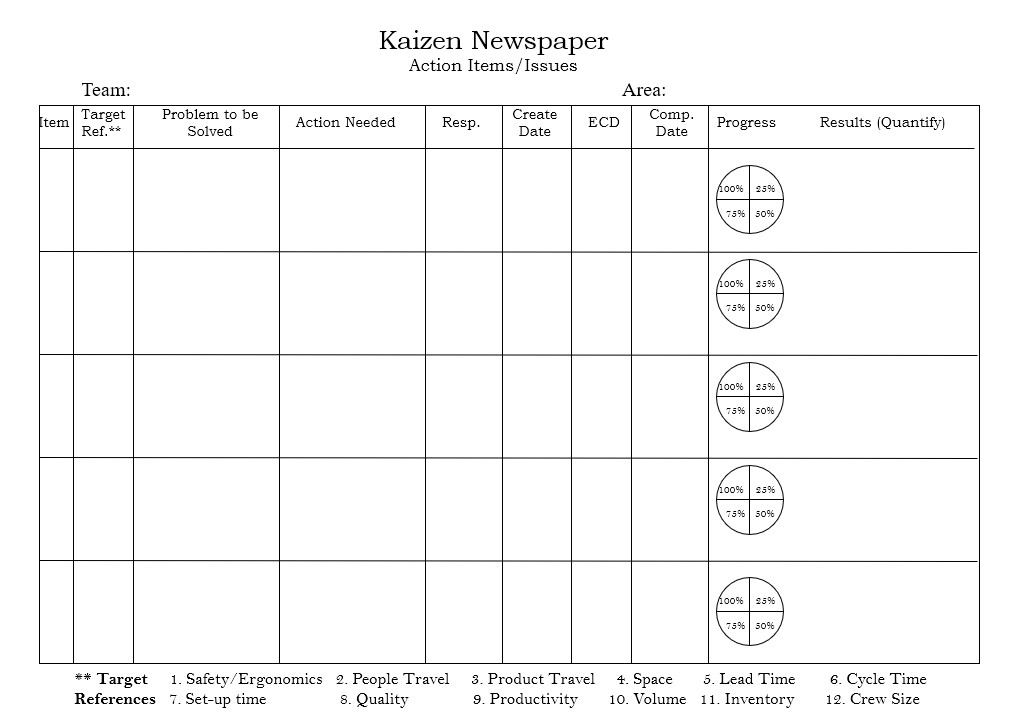

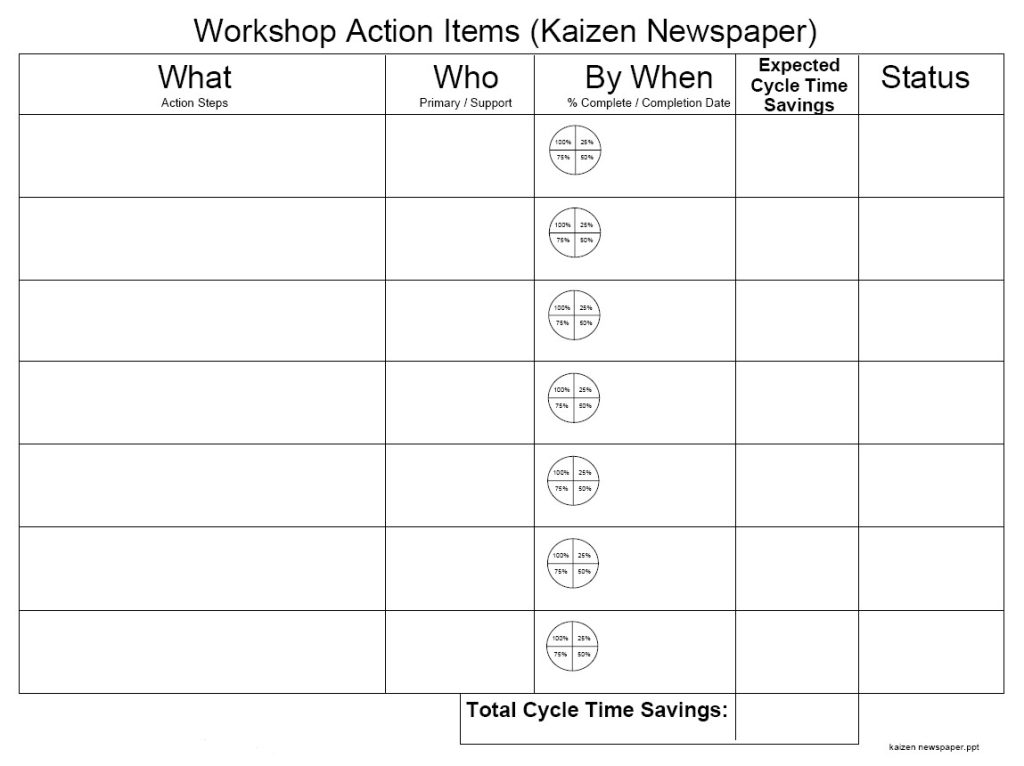

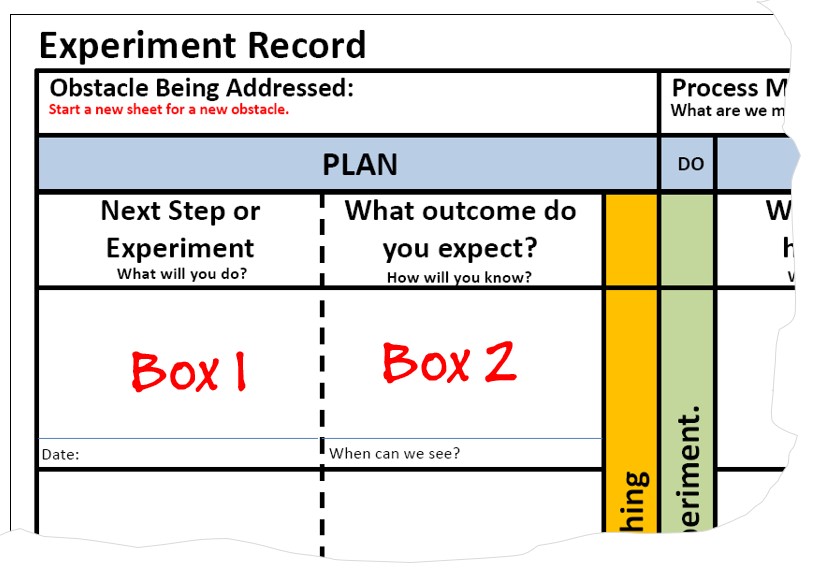

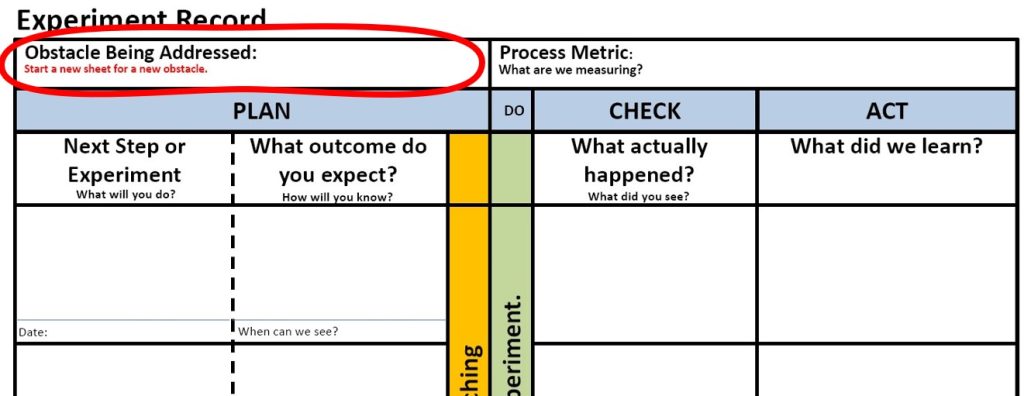

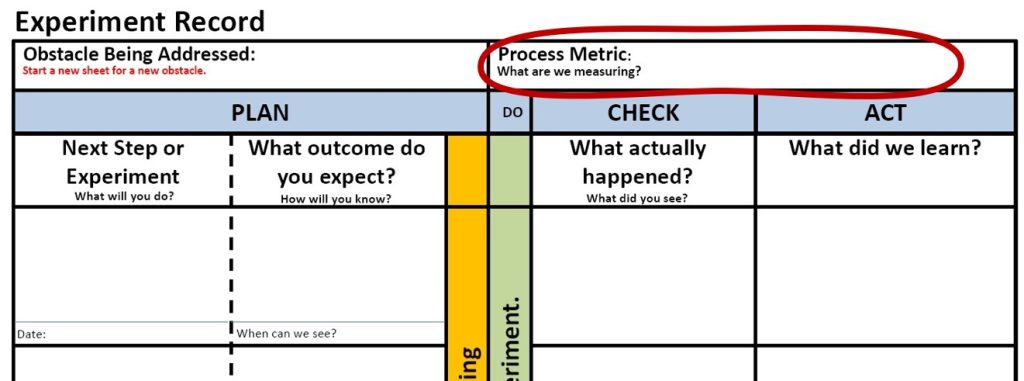

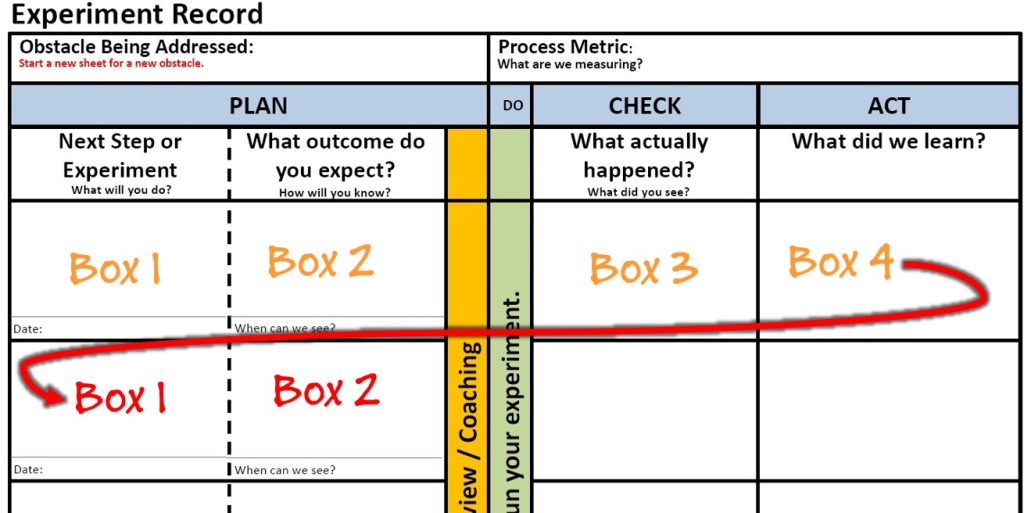

I’m looking at the Starter Kata within the Improvement Kata (the detailed steps of Grasp the Current Condition, the structure of the storyboard, the obstacle parking lot, the experimenting record to name most of them) through the same lens.

Those are structures that a beginning coach can use effectively to help their learner through the framework of improving a process through the rigor of learning and experimenting with scientific structure.

The whole goal is to get someone who is reasonably competent at using those improvement tools up to speed as coach who is, in turn, working to develop someone else to use them effectively.

And there is the key divergence of Toyota Kata. It isn’t just about solving the problem. It is about getting problems solved in ways that develop peoples’ problem solving skills. This is how we create this problem-solving culture that is so elusive in most companies.

We can’t do that by just showing people good problem solving. We have to teach it deliberately in ways that allow people to practice, with correction, the process of problem solving.

But, as I said last week, the Improvement Kata is actually neither prescriptive nor proscriptive about any particular Starter Kata.

So, if you want to use the tools from Six Sigma and DMAIC instead, go for it. But make sure you are doing so with the goal of teaching them, vs. expecting immediate competence! Be ready to work side-by-side with your learner, or break the task into smaller bits. If they are left feeling incompetent or put on the spot they are less likely to return for more learning.

This is how you can move from the culture of the “Black Belt” expert practitioner toward a culture where everyone is applying the basic structure to everything. Sending people to “Green Belt” classes isn’t going to do that on its own. There has to be structured practice using the logical structure until it is habitual. It isn’t part of the culture until (nearly) everyone talks that way.

The Coaching Kata

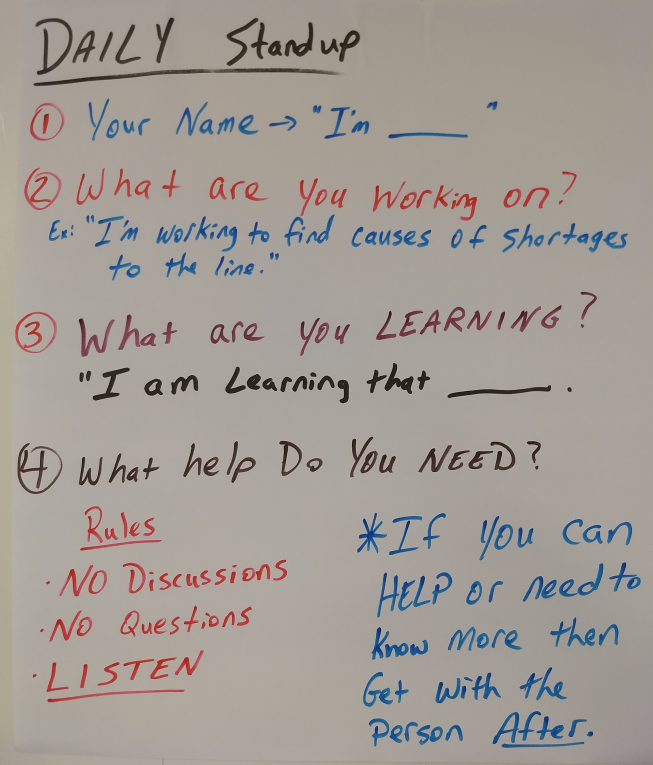

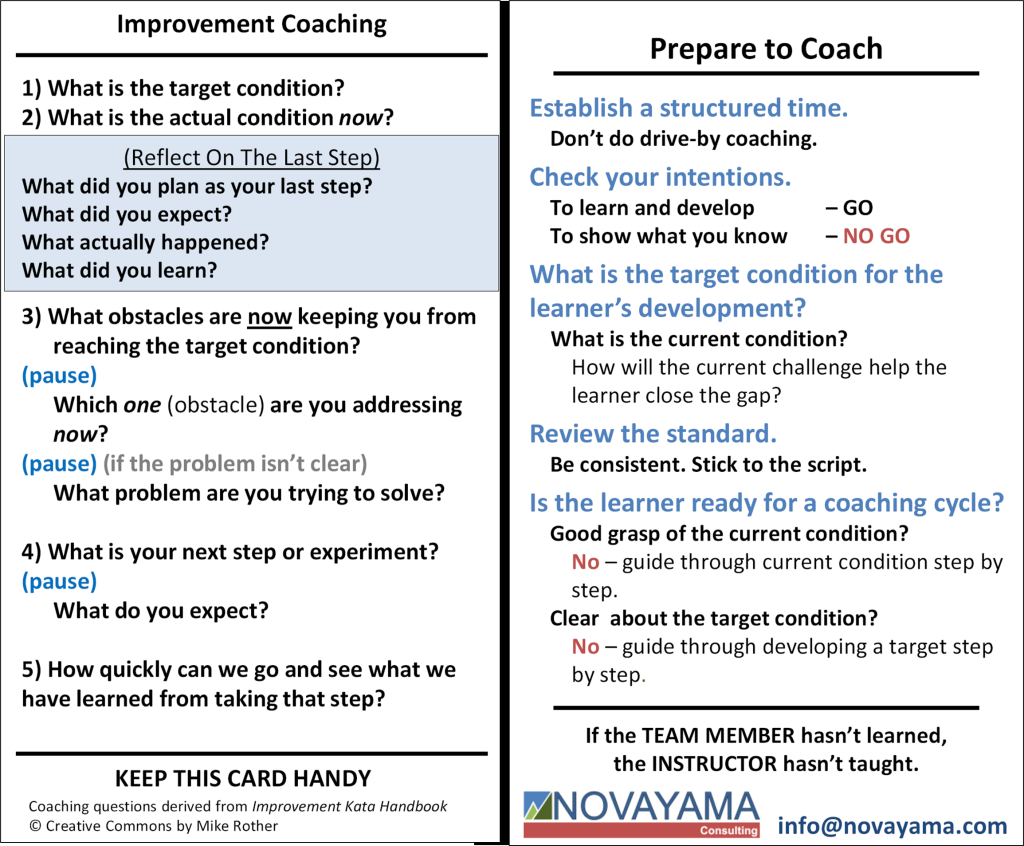

The “5 Questions” of the Coaching Kata are designed to give a minimum viable framework as a launching point for someone who is learning to coach in order to develop people’s problem solving skills.

That’s the key: This isn’t about the boss knowing the technical solution. It is about learning the mindset behind teaching and coaching someone else through discovering the technical solution. This is the part that is adaptive – the coach is often the stakeholder, and they have to adjust their behavior, assumptions, and maybe even values about what is most important for this to work well.

If they “coach” by leading with, “Why don’t you just…?” or “Have you thought about…?” they are disguising direction as curiosity.

A skilled coach is going to be patiently persistent, questioning the learner through deeper and deeper understanding, often having them go back for more understanding in the process. The coach has to know the point at which the learner starts speculating, and ask about how we are going to verify or confirm that.

If the coach sees the understanding gap, they can pull from their repertoire of things for the learner can use to gain more knowledge. That might be “build a block diagram, but let’s go watch the process so we can see what is really happening.” It might be, “Great data points, can we put them on a run chart so we can better see the patterns?”

You can’t do this in a conference room – once the threshold of knowledge is reached, the only place to get more understanding is back where things are actually happening.

But the whole point here is that we are working to establish patterns of conversation within the organization. We are working to build problem solving capability so that more problems can be solved, closer to the point of origin. This is, I think, fundamentally different than a parachuting in a professional problems solver to do the heavy lifting.

As a Change Agent

IF you are working to shift the organization’s normal patterns toward collaborative problem solving (not everyone is), then I think a Change Agent is better served by understanding (Grasp the Current Condition!) the existing problem-solving structure, and then adapting any adjustments you are thinking about to minimize the change you are asking people to make. Make those adjustments as deliberate experiments. Prepare yourself to be surprised when people respond differently than you thought they would. You can make a lot of change over the long arc, but the right now change should be based on improving something that already exists.

Contrast that with the new “Lean Program” or “Now we are going to do DMAIC” that takes everyone through classes, uses alien words with pedantic definitions. The message buried in that approach is, “You aren’t competent, and I am, so let me show you what I know.” My name for that is “Creating resistance as you go.”

If I adapt whatever terms they use, and start asking intensely curious questions that nudge things away from rote application, and deeper into actually thinking about what they are seeing and learning, then I am leveraging what they already know and building on it.

Big difference.

*Yes, for Kata purists, we have the “Planning Phase” and “Execution” (or “Striving”) phase. I’m expanding the “Planning Phase” into three “phases” each corresponding to one IK step.

**There are a few use cases where the outcome is binary. The one that came to mind was an investigation into the cause of a single incident. There isn’t necessarily a continuous metric as they converge on root cause and countermeasures in that case. Still, the underlying logical structure of that investigation is going to follow the same general pattern I am outlining here.

***What I just realized as I was reviewing this for publication is that in the years past I had been taught the basics to get a beginner skier going, but had not been taught anything else. Thus, I had been trying to apply those beginner drills in more challenging situations – without that coaching that would have helped me progress through each limitation as I pushed my abilities. In skiing terms, wedge turns don’t work on intermediate / advanced slopes. At least not very well. I was stuck as a beginner trying to use beginner’s techniques in more advanced situations.

This is an important lesson for the Toyota Kata community. The starter kata are just that. There are real-world situations that require more sophisticated tools to uncover what is actually happening. We (as coaches) have to be prepared to help if (when) a learner gets in over their head.