The Coaching Kata is much more than just asking the 5 questions. The coach needs to pay attention to the answers and make sure the thinking flows.

Although I have alluded to pieces in prior posts, today I want to go over how I try to connect the dots during a coaching cycle.

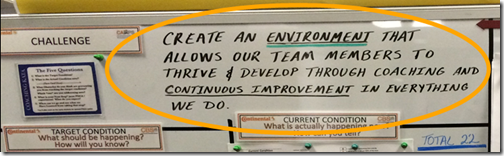

Does the learner understand the challenge she is striving for?

The “5 Questions” of the Coaching Kata do not explicitly ask about the challenge the learner is striving for. This makes sense because the challenge generally doesn’t change over the course of a week or two.

But I often see challenges that are vague, defined only by a general direction like “reduce.” The question I ask at that point is “How will you know when you have achieved the challenge?”

If there isn’t a measurable outcome (and sometimes there isn’t), I am probing to see if the learner really understands what he must achieve to meet the challenge.

This usually comes up when I am 2nd coaching and the learner and regular coach haven’t really reached a meeting of the minds on what the challenge is.

Is the target condition a logical step in the direction of the challenge?

And is the target condition based on a thorough grasp of the current condition?

I’m going to start with this secondary question since I run into this issue more often, especially in organizations with novice coaches. (And, by definition, that is most of the organizations where I spend time.)

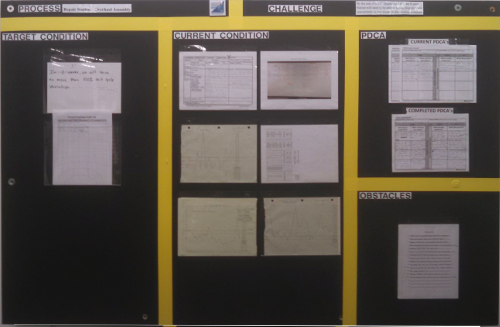

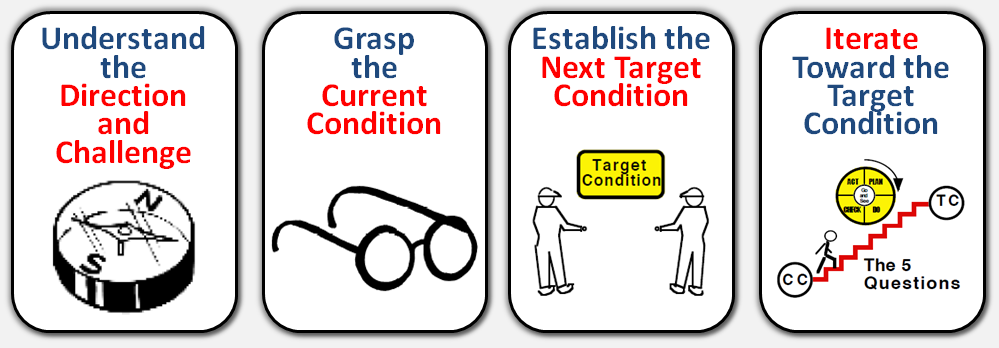

It is quite common for the learner to first try to establish a target condition, and then grasp the current condition. Not surprisingly, they struggle with that approach. It sometimes helps to have the four steps of the Improvement Kata up near the board, and even go as far as to have a “You are here” arrow.

Another question I ask myself is Can I directly compare the target condition and the current condition? Can I see the gap, can I see the same indicators and measurements used for each so I can compare “apples vs apples”?

Along with this is the same question I ask for the challenge, only more so for the target condition:

How will the learner be able to tell when the target is met? Since this has a short-term deadline, I am really looking for a crisp, black-and-white line here. The target condition is either met or not met on the date.

Is there a short-term date that is in the future?

It is pretty common for a novice learner to set a target condition equal to the challenge. If they are over-reaching, I’ll impose a date, usually no more than two weeks out. “Where will you be in two weeks?” Another way to ask is “What will the current condition be in two weeks?”

Sometimes the learner has slid up to the date and past it. Watch for this! If the date comes up without hitting the target, then it is time to reflect and establish a new target condition in the future.

Is the target condition a step in the direction of the challenge?

Usually the link between the target condition and the overall challenge is pretty obvious. Sometimes, though, it isn’t clear to the coach, even if it is clear in the mind of the learner. In these cases, it is important for the coach to ask.

Key Point: The coach isn’t rigidly locked into the script of the 5 questions. The purpose of follow-up questions is to (1) actually get an answer to the Coaching Kata questions and (2) make sure the coach understands how the learner is thinking. Remember coach: It is the learner’s thinking that you are working to improve, so you have to understand it!

(And occasionally the learner will try to establish a target condition that really isn’t related to the challenge.)

Does the “obstacle being addressed” actually relate to the target condition?

(Always keep your marshmallow on top!)

The question is “What obstacles do you think are preventing you from reaching the target condition?” That question should be answered with a reading of all of the obstacles. (Again, the coach is trying to understand what the learner is thinking.) Then “Which one (obstacle) are you addressing now?”

Generally I give a pretty broad (though not infinitely broad) pass to the obstacles on the list. They are, after all, the learner’s opinion (“…do you think are…”). But when it comes to the “obstacle being addressed now” I apply a little more scrutiny.

I have addressed this with a tip in a previous post: TOYOTA KATA: IS THAT REALLY AN OBSTACLE?

It is perfectly legitimate, especially early on, for an obstacle to be something we need to learn more about. The boundary between “Grasp the current condition” and “Establish the next target condition” can be blurry. As the focus is narrowed, the learner may well have to go back and dig into some more detail about the current condition. If that is impeding getting to the target, then just write it down, and be clear what information is needed. Then establish a step that will get that information.

Sometimes the learner will write down every obstacle they perceive to reaching the challenge. The whole point of establishing a Target Condition is to narrow the scope of what needs to be worked on down to something easier to deal with. When I focus them on only the obstacles that relate directly to their Target Condition, many are understandably reluctant to simply cross other (legitimate, just not “right now”) issues off the list.

In this case it can be helpful to establish a second Obstacle Parking Lot off to the side that has these longer-term obstacles and problems on it. That does a couple of things. It can remind the coach (who is often the boss) that, yes, we know those are issues, but we aren’t working on those right now. Other team members who contribute their thinking can also know they were heard, and those issues will be addressed when they are actually impeding progress.

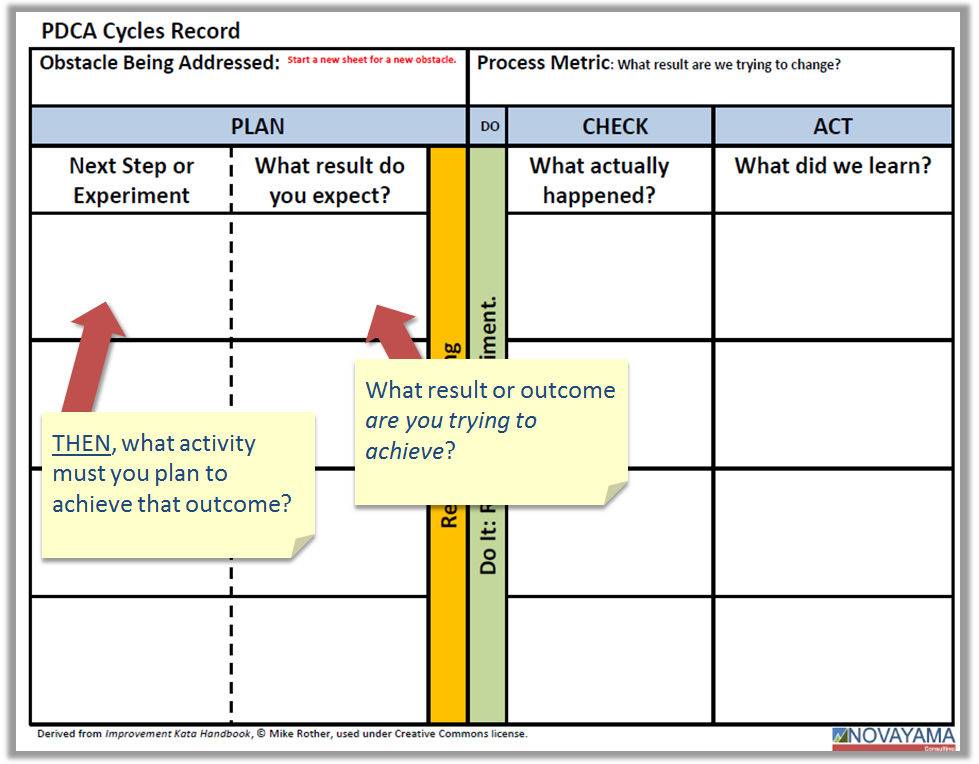

Does the “Next step or experiment” lead to learning about the obstacle being addressed?

Sometimes it helps to have the learner first list what they need to learn, and then fill in what they are going to do. See this previous post for the details: IMPROVEMENT KATA: NEXT STEP AND EXPECTED RESULT.

In any case, I am looking to see an “Expected result” that at least implies learning.

In “When can we go and see what we have learned from taking that step?” I am also looking for a fast turn-around. It is common for the next step to be bigger than it needs to be. “What can you do today that will help you learn?” can sometimes help clarify that the learner doesn’t always need to try a full-up fix. It may be more productive to test the idea in a limited way just to make sure it will work the way she thinks it will. That is faster than a big project that ends up not working.

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a

Flatly, that doesn’t work unless the culture is extremely well aligned and there is a