Darren left a great question in the Takt Time-Cycle Time post:

Question… Which system is more efficient, a fixed rigid Takt based production line or a flexible One Piece Flow?

In terms of designing a manual based production line to meet a theoretical forecasted ‘takt time’, (10 fixed workstations needs 10 operators), how do you fluctuate in a seasonal business (+/-25%/month) to ensure you don’t end up over stocking your internal customer?

Would One Piece Flow be more efficient on the whole value chain in this instance due to its flexibility?

That was a few weeks ago. Through its evolution, this post has had four titles, and I don’t think there is a single sentence of the original draft that survived the rewrites.

I started this post with a confident analysis of the problem, and the likely solution. Then I realized something. I don’t know.

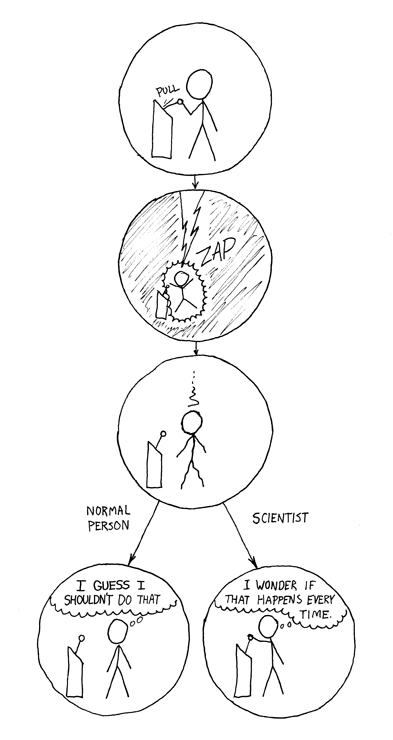

My brain, just like every other brain on the planet (human and others) is an incredibly efficient pattern matching machine. I got a little bit of information, and immediately filled in a picture of Darren’s factory and proceeded to work out a course of actions to take, as well as alternatives based on other sets of assumptions.

NO, No, no!

Our Reflex: Jumping to Solution

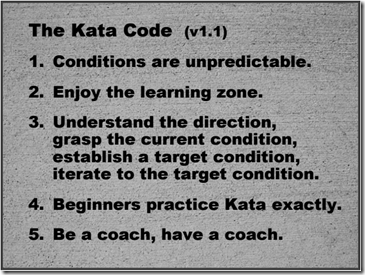

This graphic is copied from Mike Rother’s presentation material. It is awesome.

It is likely that at this point you know that it doesn’t say “JUMPING TO CONCLUSIONS” under the little blue square, and of course you are right.

But in spite of the fact that you know the truth, it is likely you still read “JUMPING TO CONCLUSIONS” when you look at the first graphic. I know I do, and I present this all of the time.

Our brains are all wired to do this, it is basic survival. It happens very fast. Think about a time when you have been startled by something you thought you saw, that a few seconds later you realized it was nothing.

That pattern recognition triggered the startle. It was seconds later that your logical brain took over and analyzed what was really going on. This is good. We don’t have time to figure out if that movement in the grass was really a leopard or not. We’ll sort that out after we get away.

Our modern brains work the same way with learned patterns  but we are usually very poor at distinguishing between “what we really know” and “what we have filled in with assumptions.”

but we are usually very poor at distinguishing between “what we really know” and “what we have filled in with assumptions.”

This is the trap that we “lean experts” (whatever that means) fall into all of the time. We take limited information, extrapolate it into a false full understanding, and deliver a diagnosis and treatment.

Boom. Done. Next?

What’s even worse is we often don’t hang around to see if the solution worked exactly the way we expected, or if anomalies came up.

In other words, everything comes down to takt, flow and pull, right? Kinda, but kinda not.

Some Technical Background

All of the above notwithstanding, it really helps to understand how the mechanics of “lean” tie together to create the physical part of an organic/technical process.

What I mean by “really helps” is this understanding gives you a broad sense of how the mechanics help people learn. Someone who only understands the mechanics as “a set of tools” is committing the gravest sin: Leaving out the people.

One Piece Flow

One piece flow is not inherently efficient. It is easy to have lots of excess capacity, which translates to either overproduction or waiting, and still have one piece flow.

This is the people part: One piece flow makes those imbalances very obvious to the people doing the work so you can do something about them, if you choose to. Many people think the goal is one piece flow. The goal is making sure the people doing the work can see if the flow is going smoothly or not; and give them an opportunity to fix the things that make flow less than smooth.

A pull system is designed to throw overproduction (or under-production) right into your face by stopping your line rather than allowing excess stuff to just pile up. Again, it is a tool to give the people doing the work immediate visibility of something unexpected rather than the delayed reporting of inventory levels in a computer somewhere.

Flexibility

Any given level of capacity has a sweet spot for efficiency. Even “inefficient” systems are most efficient when their capacity (usually defined by a bottleneck somewhere) is at 100% utilization (which rarely happens).

If other process steps are capable of running faster (which is the very definition of a bottleneck), they will, they must either be underutilized or build up work-in-process. This is part of the problem Darren is asking about – flooding his downstream operation with excess WIP to keep his line running efficiently.

If your system is designed to max out at 100 units / day, and you make less than, that your efficiency is reduced. If the next operation can’t run at 100 units / day and absorb your output, then it is the bottleneck. See above.

Now, let’s break down your costs of capacity. In the broadest sense, your costs come down to two things:

- Capital equipment. (And let’s include the costs of the facility here.)

- Labor – paying the people.

The capital equipment cost is largely fixed. At any rate of production less than what the equipment is capable of holding, you are using it “less efficiently” than you could. Since machines usually operate at different rates, it is you aren’t going fully utilize anything but the slowest one. It doesn’t make sense to even try.

People is more complicated. In the short term, your labor costs are fixed as well. You are paying the people to be there whether they are productive or not.

When the people are operating machines, your flexibility depends on how well the automation is designed. The technical application of “lean tools” to build flow cells pushes hard against this constraint. We strive to decouple people from individual machines, so the rate can flex up and down by varying the work cycles rather than just having people wait around or over produce.

At the other end of the labor spectrum is pure manual work, like assembly. We are striving for that same flexibility by moving typically separated operations together so people can divide the labor into zones that match the desired rate of production.

All of these approaches strive for a system that allows incrementally adjusting the capacity by adding people as needed. However this adds costs as well, often hidden ones. Where do these people come from, and frankly, “what are they doing when they aren’t working for you?” are a couple of questions you need to confront. The people are not parts of the machine. The system is there to help the people, not the other way around. This is people using tools to build something, not tools being run by people.

Handling Seasonal Production Efficiently

“Our demand is seasonal” is something I hear quite a bit. It is usually stated as though it is a unique condition (to them) that precludes level production. In my nearly 30 years in industry, I haven’t encountered a product (with the possible exception of OEM aircraft production and major suppliers) that didn’t have a seasonal shift of some kind.

Depending on the fluctuations and predictability of future demand, using a combination of managing backlog and building up finished goods is a pretty common way to at least partly level things out for planning purposes.

That being said, I know of at least one company whose product is (1) custom ordered for every single unit and (2) highly seasonal (in fact, they are in their peak season as I write this). They don’t have as many options.

Solving the Problem

With all of that, we get to Darren’s specific question.

The short answer is “I don’t know, but we can figure it out.”

There isn’t a fixed answer, there is a problem to solve, a challenge to overcome.

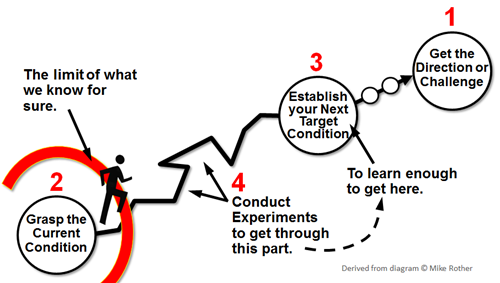

Challenge

I am interpreting the challenge here as “Have the ability to flex production +/- 25% / month without sacrificing efficiency.”

Just to ensure understanding of the challenge, I would ask to translate the production capacity targets into takt times. What is the fastest takt time you would need to hit? What is the slowest?

In other words, the +/-25% makes me do math, even if I know the baseline, before I really know what you need to be able to do. Let’s get some hard numbers on it so we will all agree when we see it, or don’t.

Remember, takt time is simply a normalization of your demand over your production time. It is a technique for short-term smoothing of your demand. It doesn’t mean you are operating that way.

Current Condition

We need to learn more, so the next questions have to do with the current condition.

While this post is too short to get down to the details, there are some additional questions I would really need to understand here.

Known: There are 10 fixed workstations with 10 operators.

Assumed to be known: The high and low target takt times (from the challenge).

How are the workstations laid out?

What are the cycle times of each operation?

What is actually happening at each of the workstations?

What are they currently capable of producing in relation to the takt times we want to cover in our +/- 25% range?

A good way to start would be to get exit cycles from each of the positions, and from the whole line. What is the current cadence of the operation? What are the lowest repeatable cycle times? How consistently is it able to run? What is driving variation?

Since we are looking for rate flexibility, I am particularly concerned with understanding points of inflexibility.

I would be looking at individual steps, at distance between the workstations, and how easily it is to shift work from one to another. Remember, to be as efficient as possible, each work cycle needs to be as close as possible to the takt time we are striving to achieve this season. Since that varies, we are going to need to create a work space that gives us the smoothest transitions possible.

What is the Next Target Condition?

I don’t know.

Until we have a good grasp of the current condition, we really can’t move beyond that point. While I am sure Darren knows much more, I am at my threshold of knowledge: 10 workstations, 10 operators. That’s all I know.

However I do know that it is unlikely I would try to get to the full challenge capability all at once. Even if I did have a good grasp of the current condition, I probably can’t see the full answer, just a step that would do two key things:

- Move in the direction I am trying to go.

- Give me more information that, today, is hidden by the nature of the work.

For an operation this size, (if I were the learner / person doing the improvement here) I would probably set that target condition for myself at no more than a week or two. (This also depends on how much time I can focus on this operation, and how easy it is to experiment. The more experiments I can run, the faster I will learn, and the quicker I can get to a target.)

Now… I will re-state the target condition to answer this question:

“We can’t… [whatever the target condition is]… “because ________.” as many times as I can. That is one way to flush out obstacles.

Another way is just to tell the skeptics we are going to start operating like this right away, then write down all of the reasons they think it won’t work.

Then the question is “OK, which of these obstacles are we going to address first?”

Iterate Experiments / PDCA to learn.

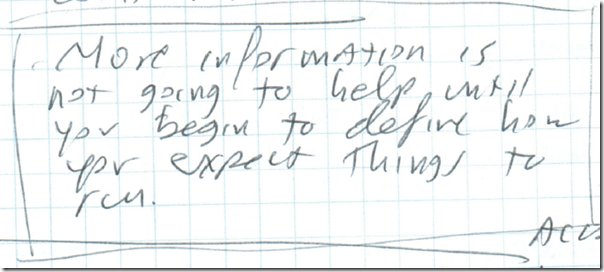

Once I know which obstacle I am choosing to address first, I need to know more about it. What do I want to learn, or what effect do I want to have on the process? Those things are my expected result.

Now… what do I need to do to cause that to happen? That is my next experiment.

And we are off to the races. As each learning cycle is completed, your current condition, your current level of understanding, changes. As you learn more, you better understand the obstacles and problems.

When you reach a target condition (or realize you are at the deadline and haven’t reached it), then go back to the top, review the challenge, make sure you understand the current condition, and establish a new target. Lather, rinse, repeat.

This Isn’t About “The Answers.”

A long time ago, when I first started this blog, I wrote a post called “The Chalk Circle.” I told the story of one of my more insightful learning experiences in the shadow of one of the original true masters, the late Yoshiki Iwata. My “ah ha” moment finally came several years later, and a year after his death. He wasn’t interested in the answers, he was teaching me the questions.

A long time ago, when I first started this blog, I wrote a post called “The Chalk Circle.” I told the story of one of my more insightful learning experiences in the shadow of one of the original true masters, the late Yoshiki Iwata. My “ah ha” moment finally came several years later, and a year after his death. He wasn’t interested in the answers, he was teaching me the questions.

We don’t know the answers to a problem like “How do I get maximum efficiency through seasonal demand changes.” The answer for one process might give you something to think about, but copying it to another is unlikely to work well. What would work for Darren’s operation is unlikely to work in Hal’s. Even small differences mean there is more learning required.

When confronted with a problem, the first question should never be “What should we do?” Rather, we need to ask “What do we need to learn?” What do we know? What do we not understand? What do we need to learn, then what step should we take to learn it? Taking actions without a learning objective is just trying stuff and hoping it works without understanding why.

What works is learning, by applying, the thinking behind sound problem solving, and being relentlessly curious about what is keeping you from moving to the next level.

I have come a long way since my time with Mr. Iwata, I continue to learn (lots), sometimes by making mistakes, sometimes with unlikely teachers, at times and in ways I least expect it. Sometimes it isn’t fun in the moment. Sometimes I have to confront something I have hidden from myself.

One thing I have learned is that the people who have all of the answers have stopped learning.

Darren – if you want to discuss your specific situation, click on “Contact Mark” and drop me an email.

Last year I nominated

Last year I nominated