The center of the B Concourse at O’Hare Airport in Chicago is dominated by a Brachiosaur skeleton, part of the Field Museum exhibit for their store there.

As a reminder for those of you over the age of 14, the Brachiosaurus was 70 feet long, 30 feet tall, weighed in at around 60 tons.* It had a brain the size of an avocado. It wasn’t smart. It wasn’t fast. Its main defense against predators was that it was simply too big to catch and eat.

In the shadow of the Brachiosaurus is United Airlines’ main customer service desk for their headquarters hub.

Back in June, Chris Matyszczyk published some really interesting commentary on Inc. Magazine’s site: The CEO of United Airlines Says He Can’t Really Make Passengers Happy

In his article, he quotes from an interview Oscar Munoz, the CEO of United Airlines, gave to ABC. From the interview:

“It’s become so stressful,” he said, “from when you leave, wherever you live, to get into traffic, to find a parking spot, to get through security.”

“Frankly,” Munoz added, “by the time you sit on one of our aircraft … you’re just pissed at the world,” and improving the flying experience won’t ultimately depend on “what coffee or cookie I give you.”

My interpretation? “We have given up trying to please our customers.”

That was the interpretation of Ed Bastian, Munoz’s counterpart at Delta Airlines:

…when Munoz’s views were put to Delta CEO Ed Bastian by Marketplace.

His response was, well, quite direct:

“I disagree. Those certainly aren’t Delta customers he is speaking to.”

My Perspective as a Frequent Flyer

Just so you know my perspective: In the course of my work, I typically purchase between 10 and 20 thousand dollars worth of airfare a year. While this isn’t anywhere near the highest, I think I am the kind of customer an airline wants to get and retain.

Further, I know the system. I know what to expect, can quickly distinguish “abnormal” from “normal” and know how to maneuver to get out in front of issues I see developing. I pay attention to weather and other events that might disrupt the system, and contingency plan accordingly. I know, generally, how to arrange my stuff to get through TSA smoothly (though they can be arbitrary).

And I have the perks of a heavy frequent flier, which buffers me from a lot of the “stuff” that casual travelers have to contend with.

Munoz used some words that really identify the problem: …by the time you sit in one of our aircraft…”

This casual statement, which correlates with my experience as a former United Airlines customer** implies a belief that the customer service experience begins once you are on the plane. This isn’t where United’s reputation is created. Once you are on the plane, the customer experience of all of the major airlines is pretty similar.

My experience reflects that it is what happens on the ground that differentiates one airline from another.

Assumptions About Customers Come True

The assumption that customers are just “pissed off at the world” and there is nothing we can do about it is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If that is the attitude from the top, then it lets the entire system off the hook for making any effort at all to understand the things that might take some of the sharp edges off the experience.

On the other hand, if the attitude is “We are responsible for the experience of our customers – even if we aren’t” then the effort can get focused on understanding exactly what kind of experience we want our customers to have, and engineering a system that delivers it to the best of our ability. That, in turn, allows reflection when we miss, and improvement for the next time.

One is a victim attitude. “We’ll get better customer satisfaction when our customers are better at understanding how hard it is.”

The other is empowering – “Even if our customers *are* pissed off at the world, we will own it and work to understand what we can do.

How Does Your System Respond to Stress?

This in my mind, is what really differentiates a good system from a broken one. Like I said, it’s easy when everything is flowing smoothly. But what happens when the system is disrupted?

Is there a mad scramble of figuring out what to do – like it is the very first time a maintenance issue has caused a flight to be cancelled? What are we going to do with all of these passengers? Process them through two people? (See the line in my photo above!)

Or is there a clear process that gets engaged to get people rebooked – leaving the true difficult cases for the in-person agents?

Ironically, the major airline with one of the very best on-time schedule records also has one of the best recovery processes. Go figure.

Then there are little gestures, like snacks or even pizza for those suffering through a long delay.

“It’s not our fault” easily leads to “you’re on your own.”

“We’re going to own it, even if we don’t” leads to “let’s see if we can help.”

Now… to be clear, the entire airline industry has a long way to go on this stuff. But my point is that some are making the effort, while others have given up.

What Experience Have You Designed for YOUR Customers?

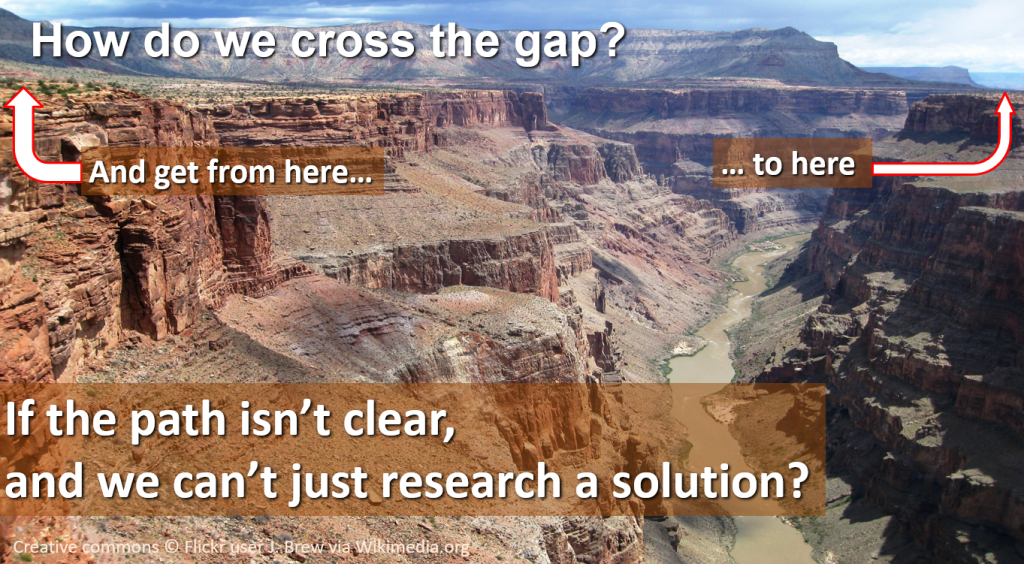

That, ultimately, is the question I am posing here. If you start with the experience you want your customer to have – a standard – then you have a point of comparison.

Did we deliver that experience? If so, then could we do it more efficiently?

If not, what got in our way, how do we close the gap?

Without a standard to strive for, there can be no improvement – and I think this is what Taiichi Ohno actually meant.

——

* Estimates of the weight vary quite a bit.

Rough metric equivalents would be around 20 meters long, 9 meters high, 50 tons. About the weight of mid-cold war era tank.

——

** With one exception that was booked for me, I haven’t flown on United since mid 2014 after an experience that could not have been better designed to tell the customer “We don’t work as a team or talk to each other.”

I cashed in my frequent flier miles for a camera about a year later.

There are lots of classes and materials out there about “active listening” but I really like a simple techniques that

There are lots of classes and materials out there about “active listening” but I really like a simple techniques that  NO sarcasm. NO implied judgement. You must come from a position of being curious about what they are trying to communicate, and what they are feeling.

NO sarcasm. NO implied judgement. You must come from a position of being curious about what they are trying to communicate, and what they are feeling.