Today was the final day of KataCon3. As I have done the last couple of days, what follows is a more or less raw stream of my notes and thoughts from the day’s events and sessions.

My notes from Day 0 (Pre-Event) are here.

Overall Thoughts

Thought I have been to a few, I rarely attend conferences. KataCon has been an exception as I have attended all three that have been held. I find it interesting that each developed a unique vibe, culture, unwritten theme.

KataCon1 in 2015 was a community coming together for the first time. “Toyota Kata” is (still) pretty new but by late 2014 there were enough people working on it to invite them together. The feeling was one of groups of people who had previously been working in isolation realizing that there are lots of others, all over the world (there was a very large European contingent) working on the same things. The ending felt like a launching ramp.

KataCon2 in 2016 had an emerging theme of “leadership development.” Overall the emotions seemed more subdued. This was a group of people coming to learn about what others were doing. The general feeling was more “technical” than “emotional.”

This year (KataCon3, 2017) the message is that “Toyota Kata” is “out in the wild.” It is evolving and adapting to different environments where it is being practiced. Overall the emerging theme seemed to be about organizations approaching the critical mass of a shift in default behavior – the ever elusive “culture change.”

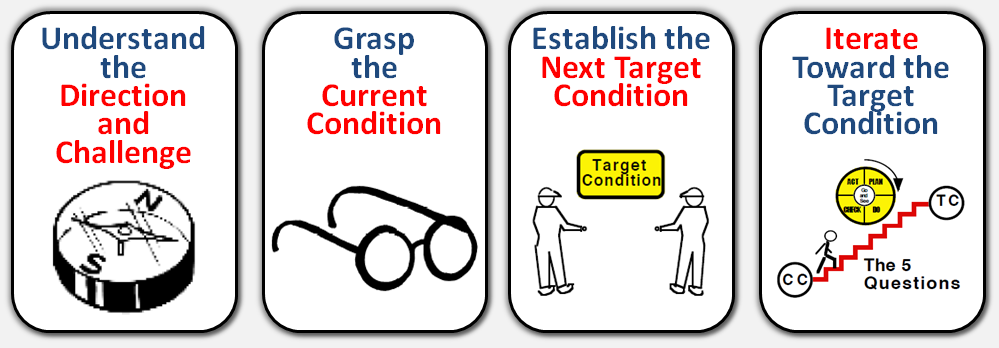

At the same time, the discussions were more nuanced. Perhaps we are moving Toyota Kata beyond the “tool age.” A realization is emerging that this is about shifting the default thinking patterns of people in an organization, and that the kata are simply teaching structure and tools to help this.

At the same time, though, I get a little concerned that organizations will believe they can let go of the structure too soon.

I am going to expand on that more in a future post about Critical Mass.

Adam Light

Adam discussed the translation between the language of Toyota Kata / “Lean” and the language of Scrum / Agile software development as well as some of the similarities and differences between the process based systems such as production, and design activities such as software development.

He pointed out that, just as “lean” has organizations doing rote deployment of the tools – without the underlying thinking and continuous problem solving – so does software development.

Though his emphasis seemed to be about encouraging kata / “lean” based customers to adopt the language of their software developers, and understand how they work, I’m inclined to say it is the responsibility of the supplier to understand the language and working patterns of their customers. Just my initial thought.

Kennametal

“You have to be a learner before you can be a coach.”

Yet another organization has made this point. They tried to skip straight to teaching others, and ended up having to back up and allow the early adopters to take the role of the learner on live processes to build basic competency (and credibility).

1300 Certified Green Belts. 100’s of lean events. Same “certified” tool applied to every problem.

Continuous Improvement was PUSHED in. Measured by:

- # of Green Belts certified

- # of events

- $ documented savings

No evidence of a lean culture.

This echoes the opening slide of my management training material (and my Toyota Kata training material).

They used Steven Spear’s HBR article Learning to Lead at Toyota to describe how they wanted to operate, then found Toyota Kata as a mechanism for learning to operate that way. (And, again, this echoes my own training material).

They noticed they had made dramatic improvements in their safety culture through implementing routines of behavior. This gave them a baseline that they could emulate to improve quality and delivery.

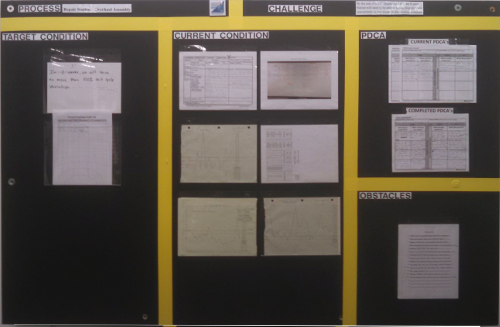

It’s not about the storyboard. – It is about the thinking behind what is written on it.

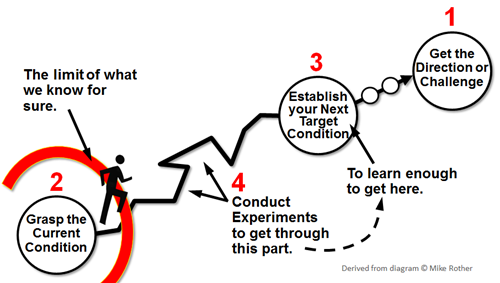

Current condition is critical before jumping to target condition. This is another very common mistake. Some teams even start with a list of obstacles – the action item mentality. This reinforces the value of having an experienced master coach to help get you started.

Optum

Mike Blaha and Dave Snider of Optum described some of the challenges in building stakeholder consensus for adopting a proposed solution that doesn’t fit their preconceived ideas.

Kata = “Show Your Work”

When a stakeholder or leader can see, or be led through, how the team arrived at a solution, they are more likely to understand. The kata experiment cycles support this process very well.

NOTE: Here is yet another reason why it is critical to be detailed when filling out your PDCA / Experiment Records. You need to be able to go back and understand, or reconstruct, your logic chain that got you to the final solution. Someone who wasn’t involved in your planning needs to be able to read the words and understand what you did and why.

Here is the coolest part. Their story actually described their process of making sure each stakeholder (who could say “no”) understood and agreed with the logical validity of their counter-intuitive proposal. During the break, I asked them if they had come across the term “nemawashi” in their original readings about “lean.” They had not.

Using the kata to solve a problem, they invented nemawashi. I have also seen teams invent SMED without any previous understanding of the process. But then somebody invented all of the so-called “lean tools” at some point. In each case it was done as a countermeasure to a specific problem or obstacle they were encountering in their effort to achieve better flow toward their customers.

Q&A Session

Mike Rother: “We have found no way to jump directly from “Aware of it” to “Able to teach it” without first passing through “Able to do it.”

- All sorts of obstacles in the way of getting leaders to practice.

- Bosch viewed constraints of leaders’ time and an obstacle and developed a countermeasure to let leaders practice when they visited the shop floor.

The question of “How to get leaders to practice” and “What about leaders that just delegate lean?” came up throughout the conference.

Many suggestions were offered, however I would add that none of them are guaranteed to work. In fact that is the case for ANY solution for ANY problem that is not EXACTLY your problem.

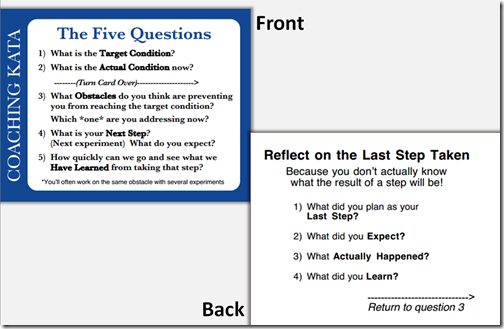

Something I have seen work sometimes (which is better than something that never works) is to reverse-coach upward. By this I mean using the format of the learner’s answers to the 5 Questions as a way to summarize status on any project. If the leader getting the report like the format, there is a possibility that leader will ask others to report in the same way. Apply the thinking to your answers when talking to the boss.

Question: How will you know this is successful? When asking about whatever change initiative is on the table, this could help clarify what the leader(s) think.

Question: Have you seen your results translate to top line growth? It was a great question, but I’m not sure anyone actually answered it. A lot of discussion about “savings” which isn’t the same.

Mike Rother: Clarification. A target condition has a hard achieve-by-date. It is experimentation with a hard deadline. It isn’t random, and it isn’t “we’ll just try stuff until we get there.” Teams don’t always hit the achieve-by-date, but they try very, very hard to do so.

Skip Stewart: When you are vague about everything, you are OK with whatever you get.

Kata in Healthcare Panel

At the end of yesterday I had planned to attend the Kata in Software Development panel discussion on the premise that it was the topic I knew least about. I changed my mind today for a number of reasons. Based on the feedback I heard from others, I’m glad I did.

In the last couple of years I have probably logged more hours in healthcare than any other environment. From that experience I predicted that although the context would be healthcare, the conversation would be about sharpening application and coaching. My hypothesis was confirmed.

Beth Carrington – Kata as achieving vs. doing. People tend to get a goal and make a list of stuff to do. Question is: What are we striving to achieve?

Challenge: Don’t use “doing” language. i.e. avoid a challenge that states what will be achieved followed by the word “by” and then how we are going to do it. Just stop at what will be achieved. That opens up many more possibilities for getting there.

“By ____(date a year from now)____ we will retain 90% of our freshmen by implementing a student mentoring program.”

“A challenge is a hypothesis that we will be tangibly closer to our vision when we get there.”

Train –> Observe –> Feedback

The method of “See one, do one, teach one” (common in healthcare) makes critical assumptions:

- There exists a common standard approach to doing it. (usually FALSE)

- That this approach works when correctly applied. (usually UNTESTED)

Obstacles are what propel you.

– Marci McCoy, Baptist Memorial Health, Oxford, Mississippi

Deployment of a new approach –> Use a real issue as a vehicle.

Experiment with something meaningful vs. a thought experiment.

Concept of non-movable obstacles. These are obstacles that are truly built into the environment or the constraints. My note: While I recognize there are truly obstacles that cannot be addressed, I would be concerned that a team may liberally use this label and constrain themselves out of success.

Deployment: Don’t push the “go” button until you are ready.

TWI is about standard behaviors (vs. standard processes). I’m interpreting as TWI is what people do. It is about how they move their hands, feet, eyes. About what they say. All of these things involve muscle movement regulated by an active brain. Those things, are by definition, behaviors. Control behavior what the brain does. (Note – this doesn’t mean we are in conscious control of all of these things). I found this an interesting way to think about it.

Use TWI to drive toward a target condition.

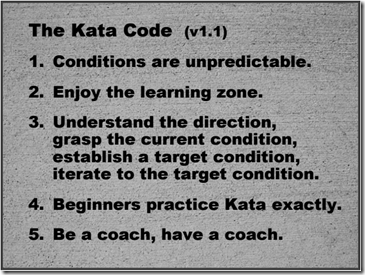

Kata = mental model. Storyboard = teaching structure. No matter what the teaching structure, the target mental model is always the same.

Process Metric: Measures “How close am I to my desired pattern of work. NOT how close am I to the goal.

We don’t PDCA to achieve the target condition. We PDCA against obstacles. This was a huge take-away insight for me. In retrospect, doh!

(Look for a post about obstacles once I get the rest of my thoughts together)

Closing Comments

“What am I doing that impedes my people from doing this?”

– Michael Lombard, CEO

About the thinking.

- Not the tools.

- Not the forms.

Last year I nominated

Last year I nominated